Revisions to the UK Investigatory Powers Act: undermining progress towards a more secure and private internet?

There is important legislation making its way through Parliament that will affect the services on offer to British consumers and businesses. The UK Government has introduced a new Bill to expand the Investigatory Powers Act (IPA), which governs how the Government can access people’s private communications for national security or law enforcement purposes. Most notably, the Bill could establish a system where the UK Home Office has a de facto veto on product development. In light of that bill, the Computer and Communications Industry Association (CCIA) has commissioned research from ORB International to test the public’s opinion on how the services they use might change. The new polling provides a broad view of people’s priorities, but in this article we wanted to look at one: privacy and security in the context of reforms to the Investigatory Powers Act.

Background – proposed changes to the Investigatory Powers Act

While responsible businesses are always ready to support legitimate law enforcement efforts, there has been a growing concern that the IPA might erode user privacy and weaken security, including by undermining end-to-end encrypted communications. There have been long-standing worries about the potential for legislation to undermine privacy through end-to-end encrypted communications and enhanced user profiling or tracking.

Reducing security and data minimization efforts by creating backdoors to encrypted data or forcing companies to maintain redundant data would pose serious risks to the overall security and confidentiality of the public’s communications and online accounts, be that people’s communications, activity or location data. This seems inconsistent with existing legal protections for personal data. Weakened security ultimately leaves online systems more vulnerable to all types of attacks. It is impossible to just build a back-door for the “good guys” — once a vulnerability exists, it will be exploited.

In the new legislation a combination of notification notices and powers to require that the status quo be maintained would risk giving the UK Home Office an effective veto on product development. This would be difficult for companies to reconcile with the push from regulators and other friendly governments to increase data protection, minimize the amount of data collected and improve security. Security fixes, in particular, often need to move fast, responding to new threats. This should be a time to increase security — not weaken it.

Cybersecurity experts writing for the Lawfare blog have sounded the alarm about the UK proposals, with Jim Baker and Richard Salgado writing:

“The proposal […] runs counter to other efforts by numerous governments—including the U.K.—to urge the private sector to find better ways to substantially enhance cybersecurity on a more sustainable basis. Instead of doing that, the bill, as currently drafted, jeopardizes data security and privacy in pursuit of an understandable goal of helping law enforcement and intelligence agencies’ legitimate objectives. But no one needs a law that could limit future progress on much-needed security enhancements, such as through the increased use of encryption. The bill needs to be fixed.”

These proposals have not been are not seen in other democratic countries, go against principles of data minimization that are enshrined in UK data legislation and could undermine all kinds of innovation. There is a real risk that companies will be caught between different regimes, when meeting UK requirements may result in breaching regulations in other friendly countries.

Over time this will push tech firms to refocus product development away from addressing the priorities of UK consumers, towards government demands for access. The obstacles the new regime creates will be a drag on innovation and therefore undermine the quality of digital services on offer. They could risk deterring investment in improving services for UK consumers and contribute to a sense that the UK is not a safe market in which to invest. The most affected services could withdraw from the UK entirely.

But what does this mean in practice and what does the British public think?

New research: public priorities for privacy and security online

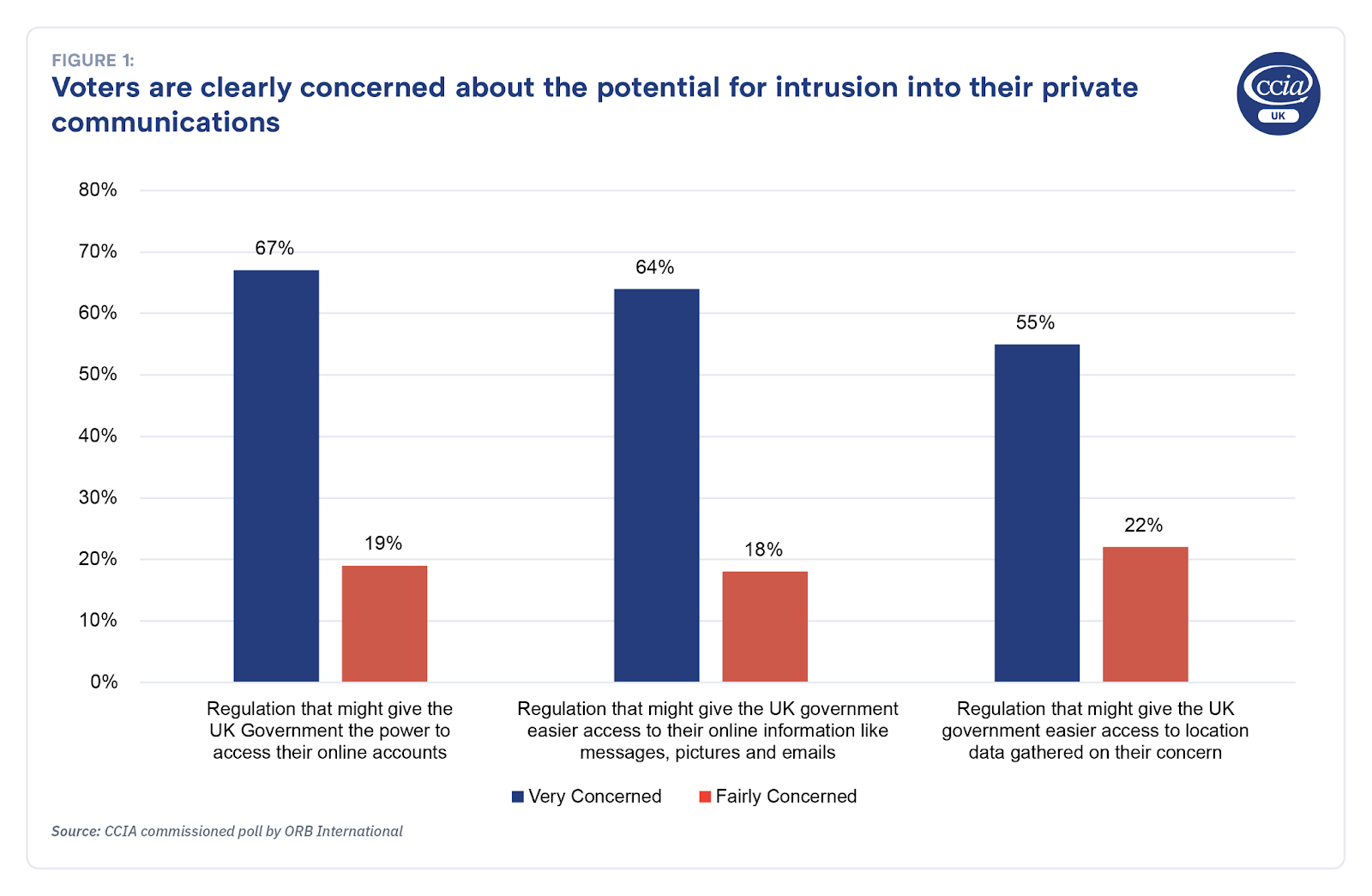

New ORB polling suggested a very broad spectrum of voters were clearly concerned about the potential for intrusion into their private communications:

This was reflected in how people described their choices online, with 50% saying privacy, data minimization and end-to-end encryption was an important factor when deciding which messaging service to use.

By contrast, levels of concern were notably more muted around justifications for a more intrusive regime. For example, 19% strongly agreed and 32% somewhat agreed with the proposition that internet companies should be required to share their data for law enforcement purposes such as policy investigations. The comparison between the set of statements where people expressed strong concerns about regulatory requirements that might infringe their privacy, and the responses to questions about various justifications for the government to have access to that data is stark. It is hard to look at this data and not see a simple result: while people are supportive of effective engagement between internet companies to address important goals like national security, they attach a greater priority to protecting their privacy.

Recommendations

There are four priorities for the next steps of the Bill:

- Give Parliament time to review the Bill. TechUK recently published its concerns that serious changes are being presented as minor adjustments and may not see the scrutiny (and potential amendments) required.

- Remove the risk of a veto on product changes. The Notices requirement should be removed or at least include the same procedural protections as the “technical capability notice” (TCN) regime. The new law should not create an effective veto on product changes, which might stifle innovation and particularly urgent security improvements.

- Address conflicts of law between the UK and other countries. The new regime should not ignore issues of jurisdiction and corporate structure in issuing requests for data. This might include making it clear that the amendments are not meant to seek EU user data under the U.S.-UK Data Access Agreement and that companies will not be in breach because of meeting requirements in other friendly countries. More broadly, the Government should only enforce these provisions in the UK for UK users.

- Include proper procedural safeguards. Operators should not be required to comply with a notice before the full appeals process is complete. At a minimum there should be a statutory time limit for appeals to avoid an indefinite halt.

Working with business to maximise security against diverse threats should be a priority for the UK Government. However the bill as it stands needs amendments. As it continues to progress policymakers must work with affected companies and privacy experts to ensure that the Bill is fit for purpose and does not pose a risk (unintentional or not) to secure communications, UK users’ privacy, or innovation and the quality of UK digital services.