The Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill – next steps for the new UK digital markets law

UK digital markets have shown their dynamism in recent years, with markets such as digital advertising seeing significant growth among formerly smaller players. However, major new legislation is going through Parliament that is intended to regulate how companies compete in the digital economy. If enacted, the UK Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Bill (DMCC) will mean the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has the most expansive powers of any regulator globally to reshape digital markets. Its decisions over when and how to use those powers will have lasting consequences which could include significant harms, particularly in the event it intervenes in digital markets too early or too broadly. The CMA is going to have to translate the broad aspirations for digital markets behind the DMCC into specific, proportionate interventions and ensure it does not inadvertently harm UK consumers’ interests or wider economic outcomes.

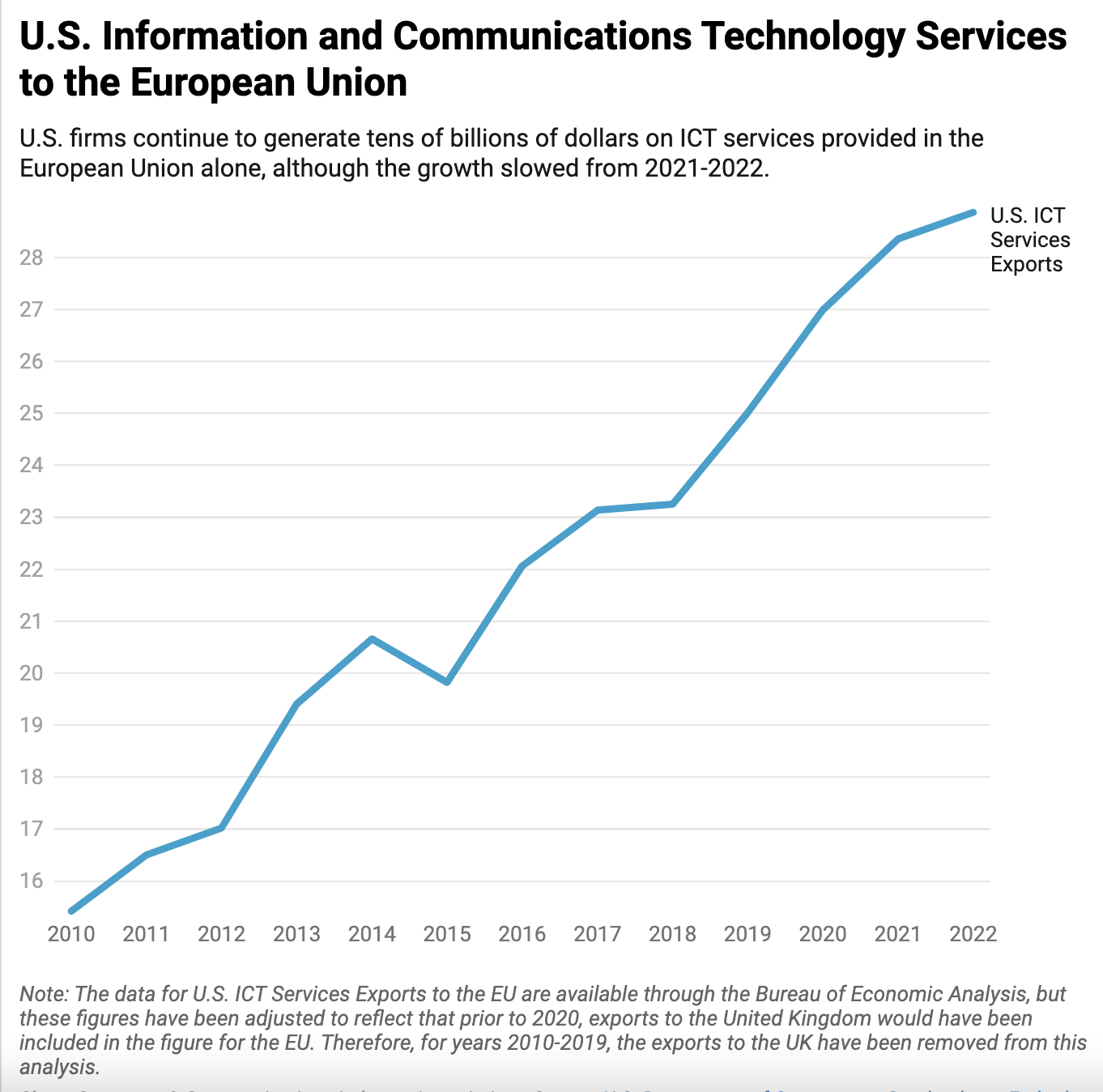

The Computer and Communications Industry Association (CCIA) recently published research that showed the potential costs if the implementation of the DMCC does go wrong, if regulatory obstacles were to delay or deter new and improved digital services being brought to market. That recent research by Europe Economics suggests the cost to consumers might be £160bn in net present value over 10 years.

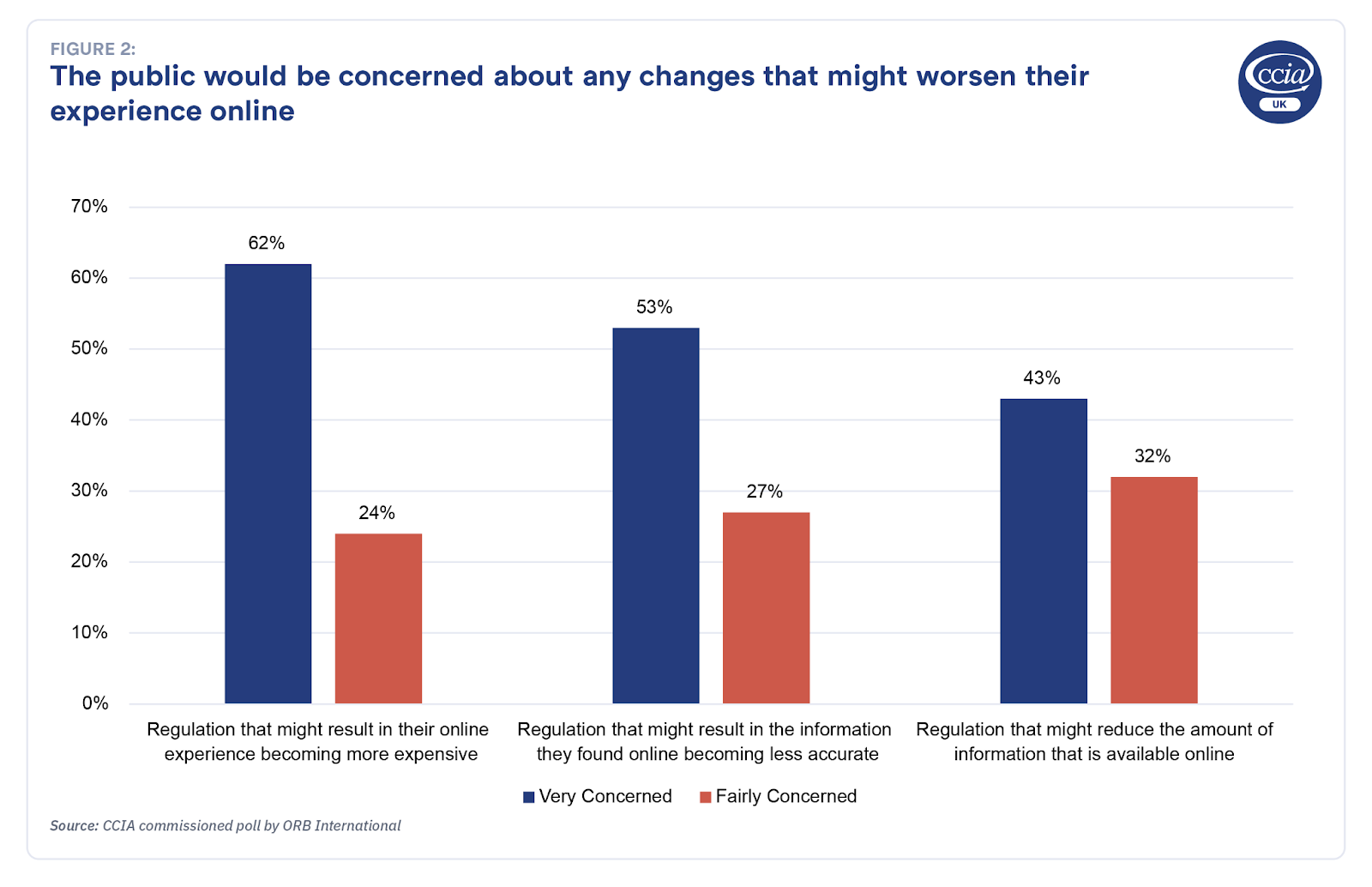

The services that will be regulated are important to consumers. New ORB polling suggests that the public would be concerned about any changes that might worsen the digital services they use online.

This polling data reflects underlying beliefs that the Government should avoid interventions that might impede innovation or access to high quality digital services:

- 46% strongly agree and 35% somewhat agree with the statement that the UK Government should not stifle technological innovation

- 42% strongly agree and 36% somewhat agree with the statement that the British Government should avoid creating obstacles to investment in new and improved internet services.

- 32% strongly agree and 35% somewhat agree with the statement that the UK should have first access to new or improved digital technologies

In light of the significance of the decisions that the CMA will be making, the Government made some attempts in the Commons to amend the law and give regulators, regulated firms and their commercial stakeholders more clarity. Those amendments have led to some concerns among Peers and it is worth exploring why and how the law is really being amended.

Proportionality

The Government and Parliament are explicitly working to ensure the DMCC achieves its objectives in the least intrusive way possible. If the same outcome can be achieved by another path that would be less onerous for regulated firms and their customers in turn, that is the best option. It therefore makes perfect sense that the regulation includes an explicit requirement for proportionality.

Proportionality is particularly important because the DMCC does not include meaningful evidential thresholds for the CMA to meet in establishing conduct requirements. Ideally the DMCC would explicitly require the CMA to go through the kind of basic steps required in DMCC for Pro-Competition Interventions. This might include requiring it to show evidence that:

- There is a problem

- The proposed intervention would address that problem

- Considering other potential costs and benefits, the intervention would benefit consumers

The Government chose not to include those requirements and instead included a weaker obligation for conduct requirements to be proportionate and to publish an assessment of consumer impact. The Government’s amendment should be understood as a relatively modest and conventional attempt to address a basic requirement that, if the CMA forces a company to change its business model, it should show a consumer harm and evidence that doing so is acting in consumers’ best interests.

Without such an amendment there is no requirement for courts to consider proportionality explicitly. Verity Egerton-Doyle argues that given requirements under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) a requirement for proportionality might be “litigated in” to the legislation, but in the legal decision over the merger between Meta and GIPHY it was stated clearly that the courts could not decide based on how the law was intended. An explicit mention of proportionality from Parliament was needed. Including proportionality explicitly gives everyone more clarity about the rules of the road and achieves exactly what Peers are looking for: a more predictable DMCC rather than one which will take shape in the Courts.

Consumer benefits defence

The consumer benefits defence has an important role in ensuring that companies will not be punished for making decisions that strike trade-offs they are confident will benefit consumers overall in complex commercial ecosystems. This exception is not there to protect regulated companies, but the interests of those consumers. To the extent regulated companies have an interest here it is because those consumers will avoid digital services over time if their interests are not protected, with everyone losing out.

The new wording after the amendment in the Commons provides clarity, which is important for newer, less mature, sectors and that means the amendment is particularly vital in the context of the DMCC. It helps mitigate the risks that the CMA inadvertently hurts the longer-term interests of consumers because countervailing benefits in these newer markets are not taken into account.

Merits review for fines

The Government amended the Bill in the Commons to provide for merits reviews with fines. Verity Egerton-Doyle at Linklaters has described this as a “sensible amendment that should reduce the need for litigation on this point (which would have been inevitable given case law on the ECHR)”. This is a reference to the case law on Article 1 of Protocol 1, which protects property including funds taken by fines.

It is important to remember that this is not a regime in which the fines are the means by which the CMA will secure behavioural change. If the CMA uses its powers (conduct requirements or pro-competition interventions) those will have effect and be in place while any penalty is decided in the courts. There will be no delay to any interventions that commercial stakeholders are looking for to improve their own position. This also limits the upside of any legal case to dispute the merits of a penalty. Dubious appeals would be expensive and risky in terms of a challenge being seen as vexations by judges and antagonising the regulator. This is again a reassurance to firms that they will have options in the event of a surprising fine, but it does not impede the DMCC functioning effectively.

“Leveraging” and protecting consumers, not competitors

There have been a number of concerns expressed about firms “leveraging” their advantages to enter other sectors. There is a huge risk that, taken too far, action here ends up protecting competitors (particularly incumbents that can best mobilise to engage with regulators). In recent years, we have seen numerous examples of the competitive constraint created by technology companies entering other technology segments, e.g. e-commerce platforms, gig economy platforms and others entering the digital advertising sector.

The risks are made clear by a recent Financial Conduct Authority call for input on the impact of data asymmetries on competition in financial services (CCIA submitted a response). The regulator is trying to anticipate risks to competition, which is understandable, but it ends up glossing over the huge actual data advantages enjoyed by incumbents it normally works with and instead focusing on speculative advantages that might be enjoyed by companies that are not even in the market. There is a huge risk that this kind of attention deters market entry and is counterproductive.

Even outside market entry, consumers generally benefit from platforms differentiating themselves, finding new ways to offer a new and better service. Of course, there will be some settings where a particular firm enjoys some advantage so vital and distinctive that this becomes a source of market power and this results in abuse that the regulator needs to step in and prevent. If we regulate prematurely or too broadly out of concern for those potential outcomes, though, we risk closing down a lot of new services that consumers want, protecting competitors rather than consumers and creating a stagnation in the market.

In a recent report, Europe Economics described the risks with not taking the importance of “supply-side substitution” and “vertical extension” seriously, in that case the lack of attention it was given in the Impact Assessment:

Not accounting for supply-side substitution, and the threat thereof, as a key contestability mechanism, the DMCC approach unreflectively deems large digital firms to have market power, and then regards their attempting to enter new markets as threatening to extend that supposed market power into new settings.

Using ex ante regulation to prevent large digital players from entering new markets, risks damaging competitive dynamics rather than enhancing them. By ignoring supply-side substitution, the risk is that intervention could inadvertently vest market power in digital players that would otherwise have to innovate and keep prices down for fear that a competitor would repurpose its infrastructure to enter their market as a challenger and replace them. Having thus created the market power they feared, competition authorities would then presumably feel obliged to create yet more restrictions to limit the freedom of action of firms that regulation itself had turned into monopolists.

Private enforcement

The DMCC currently includes a provision for private enforcement and Peers are clearly keen to protect that possibility in the Bill. There is a risk, however, that this reflects the interests of private litigation funders more than consumers and effectively functioning markets.

The Government’s goal with the DMCC is to create a “participative approach” where the CMA — and particularly its new Digital Markets Unit (DMU) — develops rules in consultation with regulated firms and other affected parties. The current blanket permission for parties to bring private court cases on issues the DMU may be considering risks wholly undermining this process. Without an appropriate framework private enforcement could:

- Undermine that consultative process, undercutting agreements between the regulator and regulated firms.

- Pre-empt the CMA’s work, with a court decision coming before the regulator has had a chance to develop effective measures through consultation and the other evidence-gathering tools it has at its disposal (which differ from those available to courts).

- Complicate the CMA’s work as it is required to monitor and potentially respond to multiple cases that parallel its own work.

CMA CEO Sarah Cardell has highlighted that these risks will be exacerbated by the role of litigation funding firms, which will have an incentive to choose the highest value cases, where there is the most widespread and well-evidenced apparent harm, which are likely to be those where the CMA is already investigating.

Potential amendments to mitigate these risks could include requiring courts to avoid conflicts and stay overlapping proceedings, or preventing proceedings where the DMU has resolved challenges over conduct. The most direct precedent, however, might be the regime under the Communications Act 2003, in which complainants are required to obtain permission from the UK Office of Communications (Ofcom) to bring private enforcement claims alleging breach of “significant market power conditions”.

Adopting a similar provision would enable the CMA to prevent overlapping cases and inconsistent outcomes. This would preserve the incentive for regulated companies to engage openly and implement quick, voluntary solutions (rather than taking a defensive litigation posture). Ofcom’s enforcement guidance states that the objective is not to prevent private actions but that “Ofcom will consider other activities it is carrying out – such as market reviews or enforcement matters – to ensure there are no potential conflicts” between public and private enforcement. The same considerations apply to the DMCC regime. Without standalone private litigation, complainants can still put their views to the regulator and / or seek judicial review where they disagree with regulatory outcomes.

This part of the Bill needs attention already because of an omission in the wording. There is a disparity between the rules for CMA regulation and this private enforcement. In the case of CMA regulation, the countervailing benefits exemption would apply. In the latter case, it has not been included. Given the importance of considering countervailing consumer benefits, this could lead to outcomes where the DMCC is not serving the overall interest of consumers, with companies not able to make pro-consumer choices without facing legal action. Fixing that issue and improving the overall framework for private enforcement could lead to a much smoother path for DMCC as the CMA works to put this ambitious legislation into practice.

Next steps

It is right that the House of Lords is giving the DMCC proper scrutiny. The next step, though, will be to reconcile where the Lords has explored changes and the Bill that passed in the Commons.

At that point, it is important to remember that the Bill that the Commons passed represented an attempt to strike a balance between those who preferred the original bill and those concerned about the expansive scope and limited checks and balances for the powers it gave the CMA. Important amendments, such as one from Robert Buckland that would have created an initial window where merits review applied so that there was external scrutiny of how the CMA developed its implementation of the DMCC, were not accepted. The Government included a requirement for the CMA to show it is acting proportionately instead of a more substantial change to include normal evidential thresholds. Reversing that amendment without other changes would recreate a situation where the regulator could intervene without showing its actions were in consumers’ best interests.

Peers should be sensitive to the risks in unwinding a compromise position struck by the Government in an attempt to reach a final Bill that everyone could live with.