Digital Trade Barriers are Spreading, Harming Strength of U.S. Exports

U.S. Digital Services and Goods Exports are a Powerhouse

The U.S. technology industry has developed into one of the country’s strongest assets for growth and export power.

The digital economy represents a notable success story for the United States, brings vast value to the domestic economy and the country’s global economic power, and facilitates the proliferation of other U.S. services that can best be exported via the Internet. Digitally-deliverable and e-commerce services were also one of the few industries to largely persist in strength during the global economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Digitally-deliverable services are an essential part of U.S. export strength, as they represented 77% of all U.S. services exports in 2021, and large technology companies earn an estimated 58% of their revenue through operations abroad.

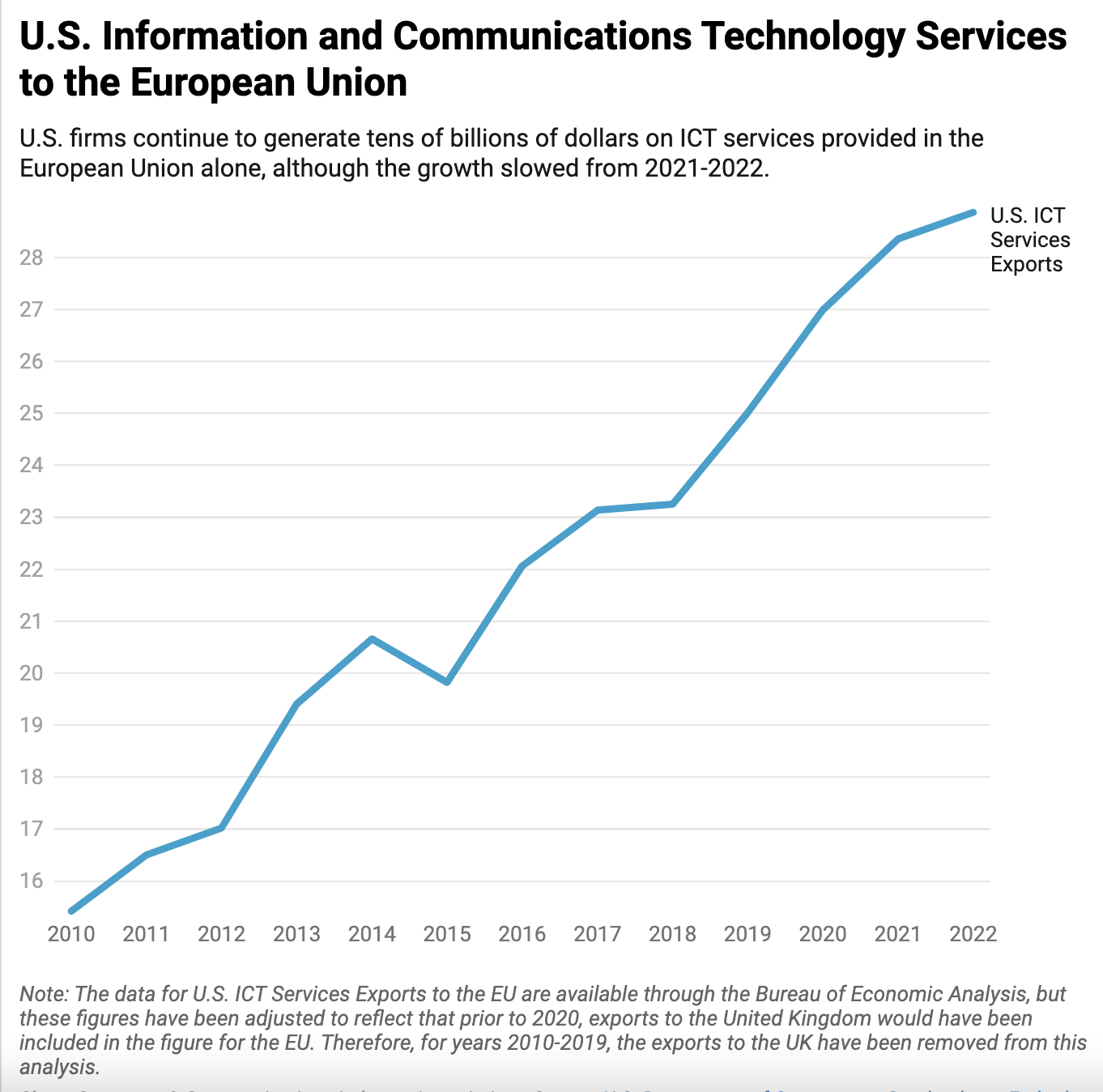

The digital economy generated $2.14 trillion of value added to the U.S. GDP in 2020, or 10.2% of total U.S. GDP, according to the most recent estimates from the Department of Commerce. The digital economy employed 7.8 million individuals, which generated almost $1.09 trillion in total compensation. The United States generated $683.86 billion globally in ICT Services and Potentially ICT-Enabled Services in 2021, driving a trade surplus of $300.6 billion overall in the industry. In fact, the United States held a trade surplus in 2021 for each region for ICT services and potentially-ICT enabled services for which data is available.

Efforts to Preference Local Industries at the Expense of U.S. Firms are Spreading Globally

Despite the vast benefits that Internet-enabled services have generated for consumers, businesses large and small, and the global economy, governments across the world have ramped up efforts to hinder online services companies with a variety of restrictions. Policymakers are pursuing laws, regulations, policies, and other formal and informal obligations that limit the ability of businesses to operate overseas and for consumers and businesses to avail themselves of the benefits of digital services and goods.

Some of these rules pursued by these jurisdictions often target a handful of companies from the U.S., either explicitly leading to a preference for local industries and upstarts or inadvertently discriminating against U.S. firms while seeking legitimate policy goals. These laws and regulations can take the shape of traditional protectionism to shield local incumbents from competition with U.S. digital rivals.

The most prominent digital trade barriers that U.S. Internet and digital exporters currently face worldwide can be classified through the following categories:

Restrictions on Cross-Border Data Flows and Infrastructure Localization Mandates

Trade in services in the modern day is simply not possible without the free flowing of data internationally. When companies are restricted from sending information to and from a jurisdiction, the provision of their services becomes either excessively costly to maintain or outright impossible. Such data flow restrictions can cost billions of dollars to both the country implementing the barrier and the firms seeking the freedom to send and receive data internationally. For example, in 2021, digitally-deliverable services exports generated $3.81 trillion globally, with the United States making up 16 percent of that figure.

Governments worldwide are intensifying efforts to implement data and infrastructure localization restrictions, which limits the ability of U.S. exporters to expand into new markets. Increasingly, countries are pursuing data protection laws, which often fail to provide for clear rules to transfer data or impose onerous obligations for data processing and storage. These localization requirements, while often in the stated pursuit of privacy and security for consumers’ personal information, belie the fact mechanisms that have been developed between trading partners that can achieve both the goals of both privacy protection and digital trade. Examples include the digital trade chapter of the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Cross-Border Privacy Rules System, and the recently-signed European Union-U.S. Data Privacy Framework.

Tightening Grip on Internet Services from Authoritarian Regimes

Governments are increasingly leveraging repressive tactics related to freedom of expression online to restrict online content as well as the operations of online platform providers, as has been covered on Project DisCo in posts in the past.

Among the most explicit barriers to digital trade are the outright filtering and blocking of U.S. Internet platforms and online content. In its 2022 Freedom on the Net report, Freedom House highlighted that over “three quarters of the world’s internet users now live in countries where authorities punish people for exercising their right to free expression online,” with a “record number of governments blocking political, social, or religious content, often targeting information sources based outside of their borders.”

There are several avenues for restricting the operations of online services providers. One of which is to shut down the Internet outright to stifle the use of online platforms, a practice that authoritarian regimes are increasingly using. Access Now reported there were 182 Internet shutdowns in 34 countries in 2021, up from the 159 shutdowns documented in 29 countries in 2020. Recently, the U.S. International Trade Commission documented that these Internet shutdowns—which have been condemned as a human rights abuse and dangerous for human life by the United Nations—also bring vast economic losses to the tune of tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, depending on the size of the market.

In some countries, repressive governments opt to block specific online platforms—often primarily from the United States—to limit political dissent, ultimately blocking operations of those services in the country. Prominent examples from just this past year include Nigeria’s indefinite ban of Twitter in 2021 that was later ruled unlawful and Russia blocking Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Soundcloud throughout 2022 to restrict information critical of its invasion of Ukraine from spreading in the country. Such tactics reflect a worrying proliferation of the “Great Firewall of China” which restricts the free flow of information and the operations of online services in various jurisdictions, potentially leading to billions of dollars in losses annually for a market the size of China.

Other prominent threats include the pursuit of heavy-handed content regulations and online platform oversight whereby governments grant themselves extensive powers to compel companies to comply with takedown orders, often accompanied with new levels of intimidation for local employees. Examples of such regimes include India’s intensifying campaign to police online services’ conduct by pushing companies such as Twitter to remove political content and even conducting raids of U.S. firms’ local offices to pressure the company to adhere to its take-down demands as well as Turkey’s expanded obligations on the use and operation of social media as part of its push to police online speech broadly through its new “disinformation law.”

Forced Payments Between Online Services and Local Incumbents in Telecommunications and News Publishing

Governments are pursuing rules to force U.S. online services providers into paying local incumbents through mandatory negotiations in circumstances where the free market has already created working relationships. In lieu of open negotiations between online services suppliers and local industry players, these frameworks implement an obligation for platforms—targeting a select few U.S. firms—to choose between paying powerful entities in local markets or exiting the market entirely. Such rules and regulations can run afoul of free trade agreements insofar as they condition operation in the market on forced revenue transfers to powerful local industry players.

Prominent examples of the past year come from the news media and telecommunications realms.

In the former category, Australia’s News Media Bargaining Code has gone into effect and influenced the advancing of similar legislation in Canada, Bill C-18, through its Parliament. Similar legislation is pending in Czechia as well. These countries have slightly varying approaches to achieve the same goal: applying rules to require online platforms to negotiate payments for news content—even just pieces of news content such as links or quotes and snippets—that are shared through their services.

In telecommunications, lawmakers in South Korea have tabled proposals to force select content and application providers to pay domestic telecommunication service providers for delivering traffic to their Internet subscribers. The calls to impose this “network usage fee” ignore the very functioning of the Internet; the vast investments online services providers have made into Internet infrastructure to improve its functionality through submarine cables, data centers, and caching infrastructure; and the fact that data that travels from content and application providers to consumers are demanded by the consumers. The policies have been found to be harmful to the structure of the free and open Internet and condemned as contrary to the net neutrality principles accepted by wide swaths of the globe, including South Korea in the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement of 2007 and the Declaration For the Future of the Internet in 2022. Academics have suggested that the idea of requiring such payments from online services providers to telecommunications providers harm consumer welfare and is unnecessary in most circumstances as well. These proposals have inspired lawmakers in the European Union to seek similar legislation, despite the bloc rejecting such policies a decade ago due to its impractical and harmful implications.

These two policy debates share one major theme in common—they seek to force paid relationships in an otherwise functioning marketplace and they focus the entire debate on a select few U.S. firms to effectively subsidize local companies that themselves enjoy vast market power.

Undermining Security in Communications

Tools like strong encryption, critical to a trustworthy digital ecosystem, are common on devices such as smartphones and are increasingly deployed end-to-end on communications services and browsers, for both consumers and businesses. Many countries, at the behest of their national security and law enforcement authorities, are considering or have implemented laws that mandate access to encrypted communications—thereby undermining business and consumer security.

For industrial policy reasons noted above, some platform regulation proposals also seek to mandate data sharing and access to core technical and operational functionality of devices. Additionally, rules various countries have implemented or are considering seek to undermine virtual private networks (examples from the past year include India and Russia), compel interception of messages on over-the-top communications services, and require unique local cybersecurity standards, all of which further harm digital security. Such rules ultimately restrict U.S. firms from operating in foreign markets since they necessitates weakening their goods and services globally, and preclude the use of standardized, scalable technologies. Such rules also undermine security for consumers, and leave them with fewer and less stable choices for personal and business communications.