The Trade Barriers Carrying the Greatest Threat to U.S. Digital Export Strength in 2023

A key pillar of U.S. export strength is the United States’ competitiveness as a service supplier around the world, an influence centered on digital technology. Digital trade is not just about the technology industry, either. Other industries that further support the trade surplus the United States enjoys in trade in services—namely financial services and tourism—are reliant on digital services and products to operate in foreign markets.

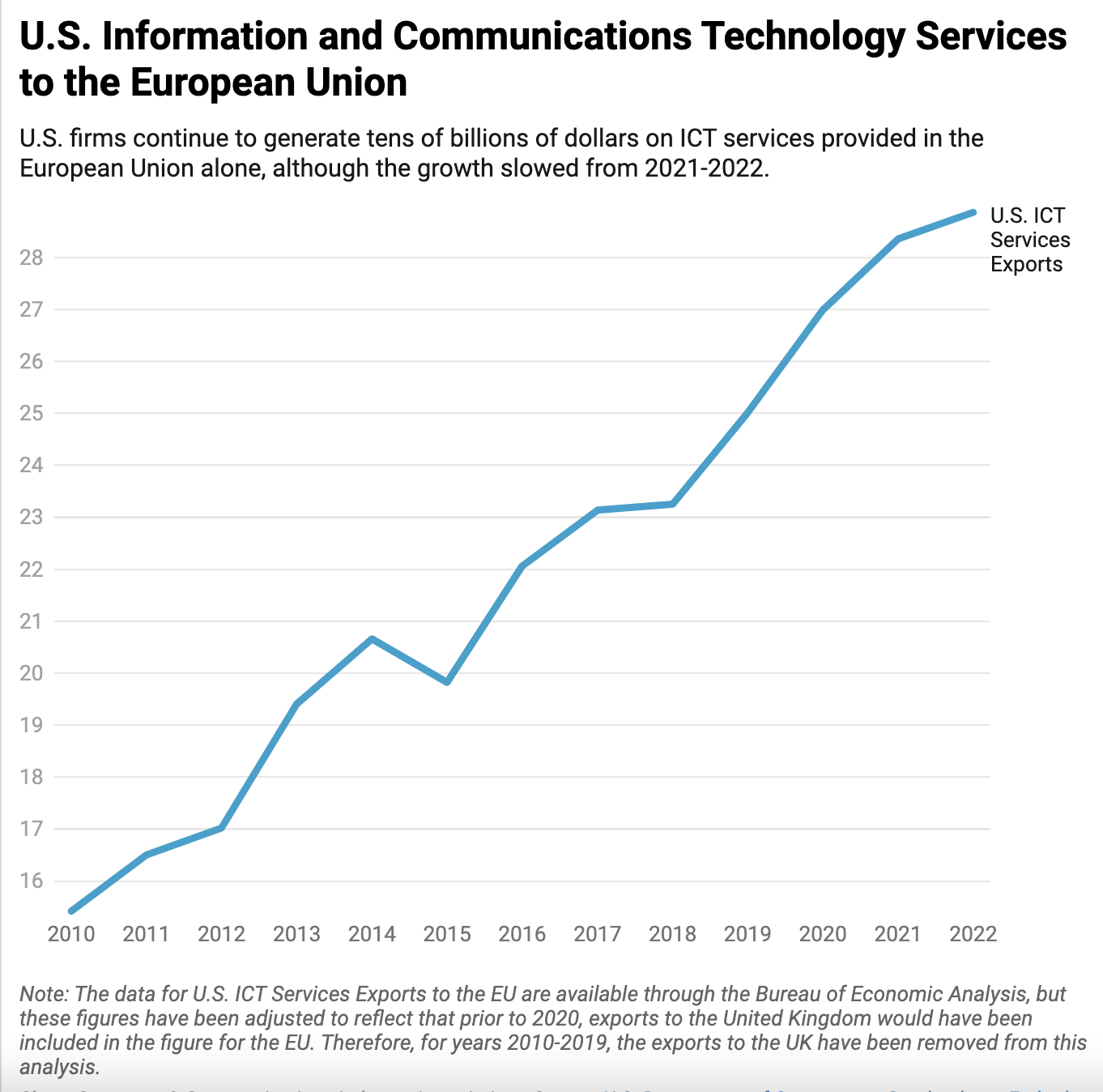

The digital economy represents a bright spot for the United States both on the domestic front and in international commerce. At home, the digital economy generated 8 million jobs and $1.24 trillion in compensation in the United States in 2021, along with $2.41 trillion in value added, according to BEA data. Through sales abroad, U.S. digital exporters brought in $626 billion from digitally-enabled services exports in 2022, up 5.5% from the $599 billion in 2021. The surplus for the United States in digitally-enabled services was $256 billion in 2022. Digitally-enabled services exports alone made up 2.5% of the U.S. GDP for 2022.

However, as the industry’s benefits have grown, so have obstacles impeding the operation of U.S. digital products and services providers abroad. The spread of complex and overlapping barriers globally threatens U.S. leadership in the digital economy and undermines U.S. exports writ large.

The barriers include restrictions ranging from traditional protectionism—such as requiring local ownership to participate in the market—to digital authoritarian restrictions that impede the delivery of services. These barriers warrant close monitoring and action from the U.S. government to protect the benefits this industry brings the U.S. economy as well as the boost it provides to indirectly-related industries such as small businesses that leverage platforms for exports, financial services providers, and other services providers that use cloud suppliers to operate abroad.

The most concerning obstacles to foreign market participation in 2023 for digital products and services suppliers generally fall into five categories, all of which are detailed below.

1) Restrictions on Cross-Border Data Flows

Cross-border data flows are the sharing of data from one national jurisdiction to another. These transfers underpin digital trade and global commerce.

Jurisdictions globally continue to pursue laws and regulatory frameworks that restrict the free flow of information across borders, leading to losses in output and productivity along with an increase in prices for industries reliant on these data transfers. These restrictions can come in the form of privacy rules that explicitly disadvantage exports, as well as burdensome requirements for the export of data generally or processing of data abroad divorced from internationally-recognized data security protocols. Countries continue to seek the implementation of data protection laws that often fail to provide clear rules to enable the transfer of data or impose unnecessarily onerous obligations for data processing and storage.

The inability to move data around the world hinders U.S. exporters large and small in all sectors of the economy from expanding into new markets. Reports have shown that data localization laws distinctly harm the economic output of the countries that adopt such policies, while also increasing the costs exponentially for both complying companies and their consumers. Cross-border data flows lead to an increase in overall exports and an 82% decrease in export costs for small and medium enterprises, while restricting the flow of data internationally is associated with damage to the national GDP and investments. The World Bank has noted that obstacles to data flows have “large negative consequences on the productivity of local companies using digital technologies and especially on trade in services.”

The United States should work with trading partners to both remove and prevent future barriers to cross-border data flows, encouraging partners to model strong commitments on the digital trade chapter in USMCA. Other digital trade agreements include explicit protections against cross-border data flow restrictions as well, including the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement and Singapore’s digital trade agreements with the UK, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and Chile. An OECD study released in May illustrates the impact digital connectivity and trade has for other sectors of both high-income and emerging economies by reviewing regional trade agreements that contain e-commerce chapters and those without such provisions.

2) Data and Infrastructure Localization Mandates and Restrictions on Cloud Services

Increasingly, jurisdictions are seeking to impose onerous and targeted requirements on foreign cloud providers—many of the most prominent representatives of which are from the United States—that limit their ability to operate in these markets. The regulations and policies pursued globally range from preferencing local upstarts at the expense of foreign rivals, to measures seeking greater ability to conduct surveillance over individuals. Governments pursue these goals through data localization policies—which harm all cross-border services suppliers—as well as making market access conditional on protectionist certification or arbitrary security standards.

The provision of cloud services globally drives billions of dollars in U.S. economic value, as cloud computing supports a wide range of subsequent industries, applications, and services reliant on cloud infrastructure and suppliers. U.S. cloud service providers are global leaders and represent a remarkable U.S. export success, supporting a trade surplus while sustaining tens of thousands of high-paying jobs for U.S. individuals. Rather than promote domestic industry, data localization policies are likely to hinder economic development, restrict domestic economic activity, and impede global competitiveness.

Key examples include rules that mandate security standards preferential to local firms in France that are being considered for the entire EU bloc, certification standards aimed at keeping out foreign competitors in Korea and Vietnam, data localization requirements in Indonesia and Mexico, restrictions on virtual private networks in India, obligations regarding content and possible interception of messages in Malaysia, and a collection of intrusive measures related to intellectual property and business operations imposed in China. These regulations are often vaguely construed, inadequately articulated and, therefore, nearly impossible to consistently implement in a non-arbitrary manner.

3) Forced Payments Between Online Services and Local Incumbents in News Publishing

A growing number of governments are pursuing rules to force U.S. online services providers to pay local news corporations through mandatory negotiations to be able to host any form of news content including links, snippets, and quotes, whose distribution is guaranteed under international intellectual property law.

These frameworks circumvent free market dynamics and the symbiotic relationship between online platforms and news businesses demonstrated by news companies posting on social media services, allowing links to be indexed on search engines, and paying for search engine optimization tools. This relationship brings news outlets referral traffic and subsequent advertising revenue. In contrast, newly-developed policies seek to implement an obligation for platforms—always targeting a select few U.S. firms—to choose between paying large local media conglomerates or exiting the market.

Key examples include Australia and Canada, where laws have been passed requiring certain online services providers to pay qualifying news publishers for the right to host any piece of news content, including links. The proposed implementing regulations for Canada’s law provide that online services providers subjected to the law could avoid designation only if they spend at least 4% of their global annual revenue, roughly attributable to the Canadian market, on local news. If every jurisdiction were to enact similar rules, the resulting payments would amount to tens of billions of dollars annually for the ability to simply index and/or host links and legally-acceptable quotes of news content. Further, such a framework would inherently undermine the information-sharing foundation of the internet, and would likely lead to other local constituencies demanding for payment from online services suppliers as well.

New Zealand has introduced a piece of legislation similar to those of Canada’s and Australia’s, while larger markets such as Brazil and Indonesia have introduced draft regulations that include the concerning remuneration rights for publishers as well as troubling content moderation restrictions that could impinge on suppliers’ ability to promote quality content and downgrade low-quality news and/or misinformation. Regulators in the United Kingdom, Japan, South Africa, and Malaysia are also looking at adopting similar frameworks to force payment by digital platforms to news corporations.

4) Experimental Platform Regulation Based on Ill-Defined Market Analysis

A general but ill-defined desire for “platform regulation,”often unsupported by evidence of consumer harm, is spurring digitally-focused ex-ante regulation around the world. In some cases, platform regulation serves as a backdoor for industrial policy dressed up as competition policy and typically employs thresholds designed specifically to target leading U.S. internet services while sparing comparable domestic or third-party services.

Such regulatory approaches depart from best practices of seeking general rules of industry-wide application, as opposed to targeting individual companies, absent credible evidence of market failure or consumer harm.

Additionally, rather than being developed through highly-prescriptive legislation, best practices also suggest that they be developed pursuant to a transparent rulemaking process that follows global norms.

In recent years, the EU, Japan, Australia, the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, and Turkey have passed or pursued untested regulatory approaches in this mold, reflecting a pressing concern that the policy is spreading before the effects of such regulations have been identified.

5) Mandatory Payments and Legacy Telecommunications Regulations for Internet-Enabled Services

Numerous governments have sought to develop mechanisms to siphon U.S. online services suppliers’ revenue to subsidize local telecommunications incumbents through mandatory payment schemes. Others have sought to impose legacy regulations from the telephony or broadband network space onto internet-enabled services, ignoring fundamental differences in these services.

One example is a proposal to force select content and application providers to pay domestic telecommunication service providers for delivering traffic to their internet subscribers, despite no evidence that such payments are justified. Such mandatory payments would hinder U.S. digital services exports and undermine the structure of the open internet that has prevailed for decades.

These types of proposals, often dubbed “network usage fees,” have begun to spread globally. Given the targeted nature of these provisions towards U.S. companies and the conditioning of market presence on payments to local industry leaders, these proposals often contravene provisions of trade agreements and WTO rules that are aimed at streamlining foreign investment and liberalizing the free flow of services. Lawmakers and regulators in the European Union, South Korea, Brazil, and countries in the Caribbean are at various stages of pursuing these fees that simultaneously impede on market access while also tampering with the free and open internet envisaged through the principles of net neutrality.

Other governments—such as India and Vietnam—have sought similar outcomes, benefiting legacy providers, by seeking to capture U.S. online services providers’ revenue and impeding market access by imposing licensing requirements or other regulations tailored for telecommunications providers.