Examining the FTC’s Hostility to Common Design Practices

Last year, the FTC released a report titled Bringing Dark Patterns to Light, which focused on design practices commonly employed online. In the report, the FTC labeled certain practices as “dark patterns” – a label sometimes applied to design practices that could trick or manipulate consumers into making choices they would not otherwise have made and that may cause themselves harm. However, many of the so-called “dark patterns” are omnipresent design elements businesses employ that consumers experience every day on sites across the internet that serve to improve the consumer experience online. As such, and contrary to what the FTC seems to believe, these design practices are not harmful to consumers. Consumers are in fact aware of many of these choices by businesses, and they are beneficiaries of the choices, not victims. The American consumer is an informed and educated consumer that understands how online retail works and how these business practices function. This piece analyzes key elements presented in the FTC’s report, as well as foundational allegations from its recent complaint against Amazon’s Subscription Services, to show that the agency’s beliefs, if implemented across the economy, could have severe ramifications for the retail marketplace and the economy as a whole.

The FTC’s report categorizes “dark patterns” by their type and variants, one of which is “misdirection”:

Using style and design to focus the user’s attention on one thing in order to distract their attention from another.

The FTC has embraced an impractical definition of “dark patterns” in this report that could be quite damaging to the retail ecosystem. The FTC’s arguments regarding these design choices are overly broad and ill-defined and would apply to an enormous range of common website practices. For example, the report discusses design features such as buttons or pieces of information featuring more prominently than others, which it contends is intended to manipulate users. Some noteworthy examples are the stylized sign-up or check-out buttons and the pricing section. Many businesses, physical and digital, naturally use style and design to focus user attention on certain aspects of their offerings over others. Businesses want their offerings to be attractive to consumers, and therefore make design choices to that effect. Before you sell a product, you first need to make it attractive to consumers and attract their attention. According to the FTC, however, an interface cannot suggest or recommend one option over another. This stance could encompass any color, size, placement, or formatting that would suggest a consumer make a certain choice over another, which would make for a bland, colorless, and unattractive shopping experience.

Many brick-and-mortar retailers engage in practices such as allocating preferred products in prime shelf space; online retailers often think the same when developing their user interface. All businesses want to attract consumers towards specific offerings, regardless of the interface used. This practice is widely accepted in physical stores, yet the FTC appears to have an issue with the same method being used online.

For example, the FTC’s complaint against Amazon alleges that

The contrast between an orange ‘double-stacked’ button to enroll in Prime and a blue link to decline prioritizes the enrollment option over the decline option and creates a visual imbalance.

The option to decline the offer is often not prominently featured on pages as no business wants their users to cancel a service. Businesses work hard to attract and maintain customers; they’re suggesting these services to consumers as they believe they have value. If a business offers a way to decline or cancel a service as prominent as the sign-up offer, that often gives the appearance that the business does not think highly of its own service. The lack of prominence is once again a normal market practice but the option to cancel or unsubscribe for a service is, nevertheless, always included.

A new study from CCIA’s research center shows that 54 percent of consumers that have a paid membership to one of the big box superstores have at least one more paid subscription to another superstore; 81% of all consumers have at least two paid retail memberships; 84% of Amazon Prime members have at least one paid big box store membership as well; and 10% of consumers have seven or more paid retail memberships. This comes to show that, regardless of the alleged lack of competition, this is a highly competitive market where consumers always have a choice as to where to get the products and services they need. Moreover, these bundled retail memberships provide enormous consumer surplus: for example, a recent conjoint survey found that just Costco, BJ’s, Sam’s Club, and Walmart+ collectively provide $1.6 billion or more in consumer surplus each year.

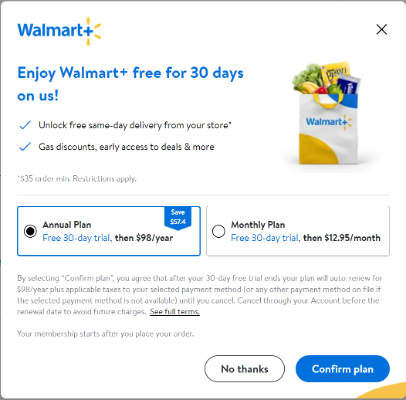

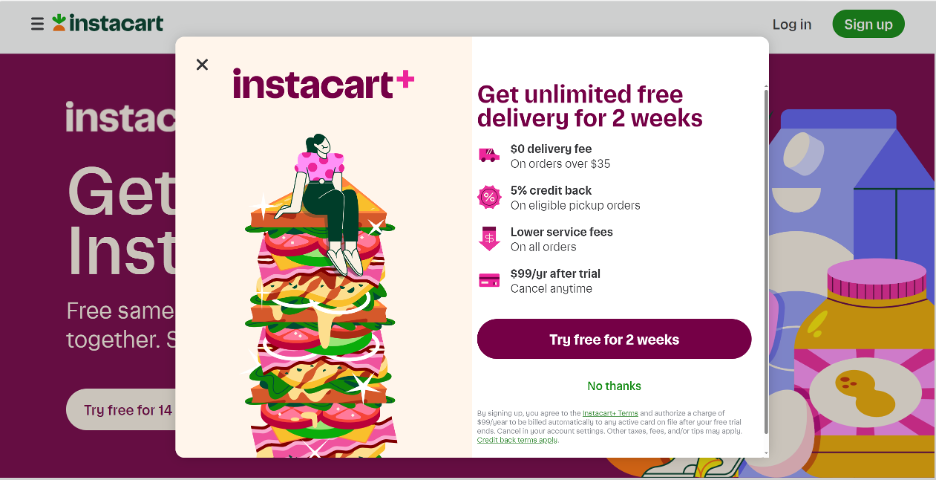

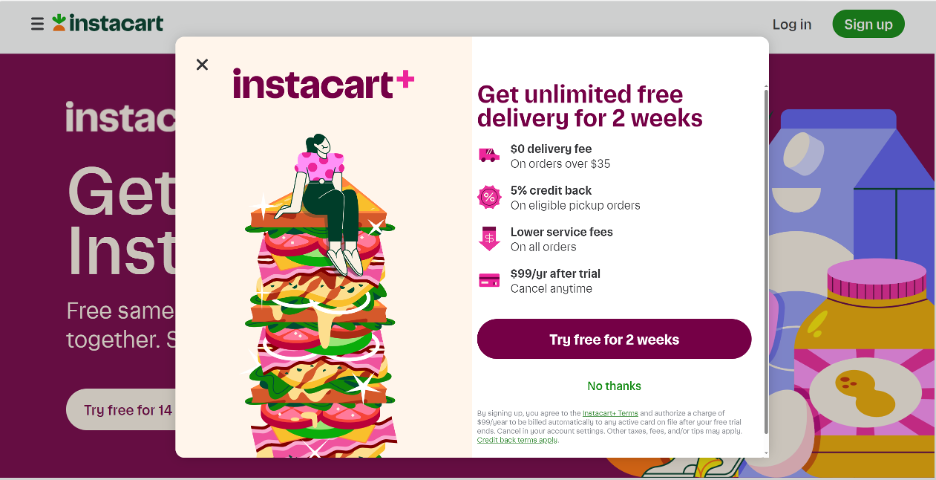

The FTC’s allegations in its recent complaint against Amazon disregard that many websites frequently have prominent sign-up or check-out buttons, banners, or advertisements. The prominent sign-up button, for example, is present on Walmart’s and Instacart’s websites as well, as it can be seen below.

Sign-up buttons are often more prominent than the button not to sign up as a simple matter of attracting users’ eyes. This not only happens in Amazon, but highlighting a recommended option is a general business practice across many companies and can most readily be found in other subscription-based retailers such as Walmart, Instacart, and others. This, in turn, is a simple and understandable usual business practice. Every company wants to attract consumers to subscribe and buy their products more than they want them not to. That is how businesses and the economy work.

Businesses must be able to promote their services in an attractive manner; if the FTC finds fault with Amazon’s practices, then many other businesses could fall under this umbrella as well. The FTC’s position fosters uncertainty in the marketplace and an unclear enforcement landscape. Of primary concern is that the FTC is not informing these services on how to construct their offerings so as to not to fall into the FTC’s overly broad and ill-defined “dark patterns.” If businesses are to respect this report, what design choices are safe? The FTC has no answer to this question.

On a similar note, the FTC’s Dark Patterns Report also highlights subsequent and repeated sign-up offers, which the FTC classifies as “nagging”:

Asking repeatedly and disruptively if a user wants to take an action or making a request that doesn’t let the user permanently decline – and then repeatedly prompting them with the request.

Viewing the issue through the lens of the FTC’s Amazon complaint, the FTC asserts that:

Amazon presents all consumers who are not Prime subscribers with at least one opportunity (also known as an “upsell”)—and often several opportunities—to join Prime before those consumers place their order on the final checkout page.

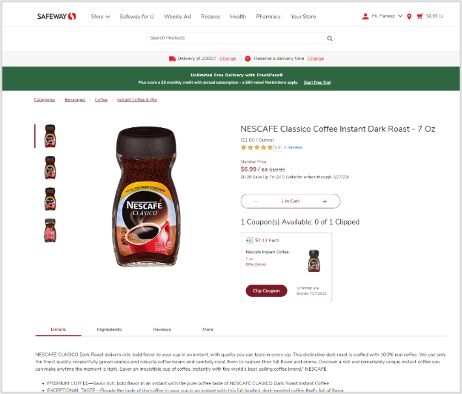

Again, the FTC’s allegations show a critical misunderstanding of how businesses operate online. Many businesses present customers with an option more than once during their time on a site. For instance, it is a common business practice in subscription-based services to offer users the opportunity to sign up for a subscription program multiple times throughout the checkout process.

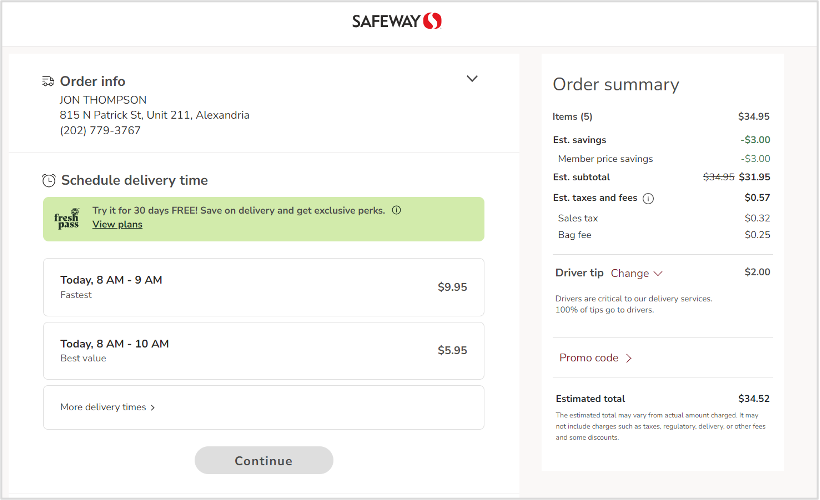

Safeway’s website (pictured below) is just one example among many that shows how companies with digital offerings include the option to subscribe from the moment the customer is shopping and up until check-out. The FTC’s objection to the practice here could apply to all businesses that ask customers during checkout if they’d like to be part of a rewards program.

This practice also extends to physical retailers, many of which engage in a similar practice when asking customers that are checking out if they would like to sign up for a membership. Retailers such as Sam’s Club or Costco even charge a membership fee for consumers to shop with them, yet the FTC has no issue with that. Retail is a highly competitive sector, businesses want consumers to come back to them instead of going to others and nagging would disincentivize that. Businesses understand exactly how far they can go to attract consumers before it becomes nagging, which would lose customers.

The FTC’s complaint against Amazon also includes pop-up advertisements as part of its “nagging” allegations, another example of misunderstanding digital markets by the agency. Innumerable businesses advertise their offerings through pop-up advertisements online, whether presenting consumers with an ad to enroll in Prime, Walmart+, or some other service. These ads might occur while the customer is visiting a company’s website with the intent to engage in their service, or using the internet for something entirely unrelated. They are the virtual billboards we all see when navigating the web. This is how advertisements work online.

The FTC’s Dark Patterns Report also discusses terms and conditions in the case they are not “adequately shown”, describing this condition as “hidden information”:

Hiding material information or significant product limitations from people.

In its complaint against Amazon, the FTC argues that on Amazon’s website the Universal Prime Decision Page (UPDP) allegedly “does not adequately disclose the price of the monthly auto-renewal feature of Prime. That information is located in small print at the bottom of the page, along with a link to the Prime terms and conditions.”

The agency further argues that Amazon places key information on a smaller font on its website. As with “hidden information”, the agency analyzes “hidden costs” as fees or other charges that people are unaware of when purchasing a product or service.

However, when businesses provide key terms of membership, items such as auto-renewal information and how to cancel, are commonly not the most prominent items on the page. Instacart, like many other companies, places this information in a less prominent position while giving a higher focus to the subscription button. Companies frequently show the program’s benefits, such as free delivery, in the largest print. Many subscription programs use smaller or less noticeable font and text size when showing customers the “terms and conditions” links and other key terms for their programs.

The report’s understanding of “hidden information” and “hidden costs” encompasses many digital services. Most subscription programs require customers to click a link to view the program’s full terms and conditions during the customer’s sign-up process, since even the most basic terms of any service require a considerable volume of text. For example, almost no subscription based program presents the full list of terms and conditions on the main website. Furthermore, these links are often in smaller font in comparison with other text on the page. This is evident on Amazon but can also be seen on the sites of Amazon’s competitors such as Instacart, Walmart, Safeway and many other businesses throughout the digital ecosystem.

This is not some scheme by businesses to trick consumers. Businesses want to make an attractive offer, not bury a customer in legal agreements concerning what they’re signing up for. Customers are more likely to want to sign up for a service when its key elements are summed up in an easy to understand and attractive package rather than if they were to have to read through pages of legal documents specifying the exact nature of the service. Notifying consumers of the potential offerings in an easily digestible manner does not harm consumers, it only enhances the consumer experience by making it easier for them to receive better offerings.

The FTC’s complaint also touches on free or discounted offers to trick consumers into a subscription which, as the agency’s Dark Patterns Report states, is a hidden subscription or a forced continuity. According to the FTC’s allegations, this occurs when there is an:

Offering of a free trial and at the end of the trial, automatically and unexpectedly charging a recurring fee if consumers don’t affirmatively cancel or offering a product for a small one-time fee, then automatically enrolling people into a subscription or continuity plan without their consent.

In the digital ecosystem, businesses frequently offer either a free trial or a monetary discount for an initial term, which are often featured prominently for first time users. This is a way for consumers to test the product and decide whether they like it and want to continue the subscription, or not. Free trials that convert into paid subscriptions are a widely practiced business model that extends across the economy. Again, this practice does not harm consumers, it enhances the consumer experience.

The FTC’s definition of ‘dark patterns’ is incomprehensible and impractical. The sweeping definition encompasses design practices omnipresent across the internet that websites use to make their offerings attractive to consumers. Furthermore, the FTC does not inform companies what they need to do to avoid practicing ‘dark patterns’ and comply with any new FTC actions.. If the FTC wishes to label these practices as “dark patterns” and intends to combat them through rulemaking and lawsuits such as its current case against Amazon, it will do so to the detriment of countless businesses simply offering attractive and competitive services, harming businesses, consumers, and the retail ecosystem.