Debunking the Myth of the “Retail Apocalypse”

News reports from late June that Toys “R” Us will soon close its 700 remaining U.S. stores played into a commonly accepted narrative about the death of traditional retailing. Hardly. We observed earlier this year that, in light of impressive 2017 Holiday Season sales results from Target, Best Buy and other retailers, the simplistic prediction that Amazon.com “will ‘kill retailing’” is “flatly wrong.” Developments since then totally confirm that it is retailers who fail to grow and adapt to the digital economy — just the latest business challenge in that economic sector over many decades — that are at risk.

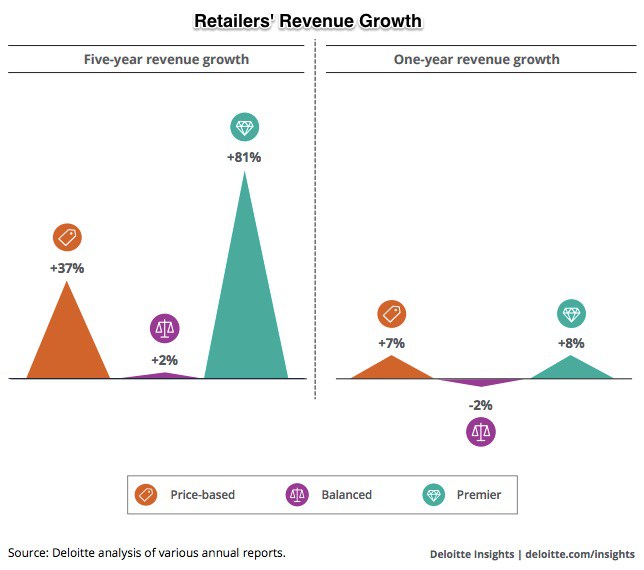

Consulting and tax firm Deloitte US released its latest perspective on the retail industry, titled The Great Retail Bifurcation: Why the Retail ‘Apocalypse’ is Really a Renaissance. The noteworthy findings make clear it is only brick-and-mortar companies in the middle of the price spectrum, dubbed “balanced” retailers, which are doing at all poorly:

Premium retailers have seen their revenues soar 81% over the last five years, while price-based retailers have seen their revenues steadily increase 37% over the same period. This contrasts with balanced retailers, whose revenue has increased only 2%. What’s more, consumers are more likely to recommend premier or price-based retailers than balanced, suggesting that retailers at either end of the spectrum are more in tune with the changing needs and are better at meeting the expectations of consumers than those in the middle.

The National Retail Federation commented in response that “[w]hile there are those who would have us believe that the retail industry is on the verge of collapse, Deloitte’s findings indicate the industry is on the verge of something very powerful and positive — a renaissance, not an apocalypse.”

This follows NRF’s cogent report last year that even in “the supposedly beleaguered department store sector, just as many businesses are opening stores as are closing them.” (Indeed, recent Census data shows total retail sales in 2018 up 5.4% over the same period last year.)

Which points to one of the basic problems with stories, like many accompanying the Toys “R” Us bankruptcy, that imply or present as fact that Amazon is causing major retailers to fail. The reality is far different. As Bloomberg explained:

On one level, the announced liquidation (at least in the U.S.) is yet another familiar story about the sorry state of old-school retailing. On another, it’s a tale of how private equity has, in many cases, worsened the industry’s upheavals. Sports Authority, Gymboree, Payless Shoesource, Claire’s, J. Crew: All these chains, and more, have struggled to adapt to the fast-changing landscape after being taken private.

The issue for so many retailers is that, having taken on huge debt loads in leveraged buyout, “going private” transactions, their debt-service obligations now dwarf cash flow. For Toys “R” Us, that amounted to an astonishing $400 million a year, in interest alone, on $6 billion in debt from a 2005 going private deal. “Who killed Toys ’R’ Us? Financialization… Financial firms acquire thing-makers or sellers like Toys “R” Us by taking on huge debt to buy them that they off-load onto the company by selling off its best bits, then remainder the skeleton or bury it in bankruptcy.” According to Walter Loeb in Forbes, this was a simple case of “an unaffordable debt burden.” Or as the Wall Street Journal described in somewhat more tempered language, Toys “R” Us and other private equity-backed firms “failed to find a profitable exit path as onerous debt restricted their ability to respond to competitive threats.”

That is the same cause underlying announcements this spring by regional supermarket chains Tops Markets and Southeastern Grocers that they too would be closing shop. It’s not Amazon or its new Whole Foods subsidiary, but instead “enormous” debt loads, the result of management by private equity firms, which has made it impossible to invest in new technologies, store formats and product lines “because they are saddled by high interest payments.”

Likewise, store closings themselves are not actually a sign of fundamental trouble in the retailing sector. When Footlocker announced plans to close more than 100 stores, CEO Dick Johnson slammed reports that pointed the finger at the “retail apocalypse.” He said in May that the retailer had shuttered 1,000 stores over the past 10 years, not an unusual move, citing a surplus of mall and retail space in the U.S. as the justification. That’s consistent with Cowen & Company research showing that the United States has 40% more retail shopping space per capita than Canada, five times more than the UK, and an astounding 10 times more than Germany. And for Footlocker getting smaller seems to have worked: sales per square foot, gross margin per square foot and “everything else has improved” as Footlocker closed stores.

Clearly, successful retailers are “racing to keep up with what feels like a series of epic shifts in consumer preferences.” Part of that is working to increase the big data aspects of consumer engagement, where online sites have long had an advantage. Footlocker, once again as an example, coupled a focus on in-store customer experience with “preparation for an increasingly digital world” by investing in technology to increase its ability “to analyze and use data.” Another part of successful retailer strategies is to maximize the differences inherent in traditional retailing. A Harvard Business Review study, for instance, found that for apparel, in-store transactions still account for almost 80% of clothing purchases today. That foot traffic simply belies claims that Amazon or online shopping is destroying traditional retail firms.

But maintaining foot traffic does not mean resting on laurels, instead it requires embracing change. One of the largest changes to emerge has been omnichannel retailing. Target is one large chain implementing an omnichannel retail strategy extremely well.

Target’s omnichannel fulfillment initiatives are cooking. It isn’t relying on the old model of putting the goods on shelves and hoping to lure customers. Instead, it is offering customers a bounty of options including free two-day delivery, same-day delivery, drive up and its Target Restock program, which gives customers the opportunity to shop over 35,000 food and essential items that are delivered the next day. Restock is also free for Red Card holders and recently cut the delivery fee to $2.99 from $4.99 with no upfront annual fee.

The lesson, as we concluded this winter, is that to prosper in an age of online competition, retailers can either get with the program, like Wal-Mart, Target and other successful merchants — which works — or continue to pursue yesteryear’s strategy by selling (and ultimately defaulting) to risk-arbitraging junk bond traders. Private equity has a valuable place in any modern economy, but too much of anything is a bad thing. Indeed, Bloomberg has highlighted the “explosive amount of risky debt owed by retail coming due over the next five years.” For retailers, over-leveraged balance sheets, immense debt service obligations and a failure to adapt to changing consumer preferences are clearly far more significant than anything Amazon has done.