Cloak Your IP Address, Expose Yourself To Legal Jeopardy?

One of the oldest networking tricks in the book may also be one of the newest digital crimes in it. And you may have to commit this particular trespass to get access to your online purchases.

One of the oldest networking tricks in the book may also be one of the newest digital crimes in it. And you may have to commit this particular trespass to get access to your online purchases.

On Friday, a district judge ruled that Craigslist could legally deny access to its site from a San Francisco Web-development shop called 3taps that helped others sites provide custom interfaces to Craigslist listings–and that 3taps had no right to circumvent that block with a proxy server that cloaked the Internet Protocol addresses of its computers.

The opinion in Craigslist, Inc. v. 3Taps, Inc. from Judge Charles R. Breyer of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, turned on the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

The CFAA has been many people’s least-favorite Internet law–a prosecution under it apparently led Internet activist Aaron Swartz to hang himself last winter–for its absurdly generic definition of computer trespass.

In particular, subsection (a)(2) of this 1986 law targets anyone who “intentionally accesses a computer without authorization or exceeds authorized access, and thereby obtains [….] information from any protected computer.”

Judge Breyer’s opinion essentially shrugs in agreement with phrasing that exhibits the regrettable combination of being overly broad and clearly written.

As he noted: “Congress apparently knew how to restrict the reach of the CFAA to only certain kinds of information, and it appreciated the public vs. nonpublic distinction–but §1030(a)(2)(c) contains no such restrictions or modifiers.”

And since Craigslist named 3taps in a cease-and-desist letter before blocking its computers’ IP addresses, that settles it.

But what if a site doesn’t address people by name when telling them to go away?

Bring up the “Live Streaming” page of the news network Al Jazeera. Until Tuesday, you could watch real-time video of its English-language coverage. Now it tells would-be Web viewers that the feed “is no longer available in the U.S.,” thanks to its launch of a new, U.S.-market cable and satellite channel called Al Jazeera America.

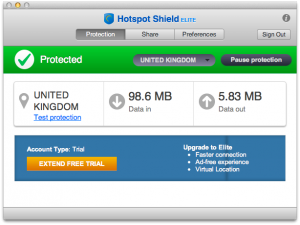

That statement is, strictly speaking, false. The old feed is very much available in the U.S. to anybody who uses a proxy server. I installed one such program, AnchorFree’s Hotspot Shield, opted into a free trial of its “Elite” service, selected a United Kingdom IP address, and moments later was watching “AJE” live online.

Was it a CFAA violation to route around AJA’s decision to block U.S. Web streaming in favor of a smaller but possibly more lucrative pay-TV audience? By the text of this law, one could argue yes.

Now consider Georgetown University professor Jim O’Donnell, who encountered a glitchy update to an e-reader program on his iPad while traveling in Singapore. O’Donnell wrote on a mailing list that after this Google app had updated itself, “all of my books had un-downloaded and needed to be downloaded again.”

Except they wouldn’t in Singapore, because Google’s e-bookstore doesn’t do business there.

O’Donnell had the luck to have only lost free, public-domain titles, so he could visit the Internet Archive’s collection of out-of-copyright titles to download new copies.

But if this glitch had taken out purchased books, his easiest and fastest remedy would have been to jump on a proxy server that would give him a U.S. IP address.

It’s hard to think of an online retailer so stupid as to sue its own customers for using a simple workaround to recover access to their own purchases. But companies have been known to be dumb on the Internet.

And the CFAA doesn’t say you have to be an elite hacker to be guilty of computer trespass. It just says you have to connect to a server without permission or without sufficient permission; as crazy as that seems, it requires no special trickery or exploits on your behalf.

In other words, the CFAA–even more so than the unbalanced anti-cirumvention provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act–is Congress’s gift to commercial control-freakery. It allows private actors to draw a line wherever they see fit, then bring the hammer of criminal prosecution down upon those who would step over it. Great business if you can get it, but I can think of many better uses for my tax dollars.