Copyright’s Laffer Curve, or, Why the Republican Study Committee Was Right

Late Friday, the Republican Study Committee (RSC) released a striking Policy Brief critical of current copyright law, authored by Derek Khanna. By Saturday afternoon, however, it had retracted the report, claiming the document had “been published without adequate review.”

The report acknowledged that copyright increasingly favors the interests of corporate rights-holders, not artists, and that as a government-created subsidy, copyright was, at best, poor approximation for either property or free markets. It urged reforming statutory damages, reinforcing the fair use doctrine, penalizing rightsholders who make false copyright claims, and – most interestingly – requiring renewal of copyright, where fees would be indexed on the revenue generated by the work.

Such aggressive proposals were likely to have offended politically powerful copyright holder constituencies, although they are not entirely novel. Numerous reforms have been urged in this nature, and even the former Register of Copyrights had acknowledged that copyright term was too long, and that Congress had made a “big mistake” with the last extension.

Some media reports implied that this might be out of step with Republican philosophy. This is exactly backwards: a conservative philosophy should always regard IP warily, as it manifests aspects of two things that conservative philosophy has traditionally abhorred in excess: taxation and regulation. These two subjects are explored after the jump.

Copyright’s Taxation Policy

The RSC paper repeatedly returns to a tax-and-subsidy way of conceptualizing copyright, which is a useful (although not new) framework. At least as early as 1841, Thomas Macaulay argued in the British House of Commons that

[t]he principle of copyright is this. It is a tax on readers for the purpose of giving a bounty to writers. The tax is an exceedingly bad one; it is a tax on one of the most innocent and most salutary of human pleasures; and never let us forget, that a tax on innocent pleasures is a premium on vicious pleasures. I admit, however, the necessity of giving a bounty to genius and learning. In order to give such a bounty, I willingly submit even to this severe and burdensome tax.

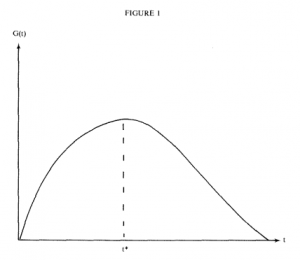

Copyright was a necessary evil, Macaulay concluded, a required subsidy for authors. But it was a tax nonetheless, and thus should be imposed no more than necessary. In fact, copyright even manifests a sort of “Laffer Curve,” a well-known model for conceptualizing taxation. This curve is an idea often attributed to economist Arthur Laffer, but should probably be attributed to Jules Dupuit in 1844, or Edmund Burke in 1774, or any number of others, who, alas, never secured the exclusive rights to own optimal tax policy.

The curve represents the idea that the amount of total tax receipts will rise to a point and then decline as tax rates increase. Starting at a tax rate of zero, the theory goes, the government collects nothing. At a taxation rate of 100%, the government similarly collects nothing, for there is no incentive to be industrious and thus no activity to tax. At nearly every point between, some amount of taxable activity occurs, which means we have a backward-bending curve. Stated otherwise, the amount of tax receipts gained from increasing rates is ultimately outweighed by the fact that rising taxation disincentives activity. Of course, the exact shape, contour, and midpoint this curve (where “optimal taxation” theoretically lies) will have dramatic distributional consequences within a society, and thus the concept remains the subject of great debate. (Indeed, even Blinder’s image at left should not be regarded as ‘to scale.’)

The fact remains, there is consensus that tax rates and receipts share a relationship. A midpoint on the curve exists. We see the same phenomenon in intellectual property. If one has no protection for creative work, little creative work will be produced. (Strictly speaking, it is not true to say no creative work, since we know some creative activity is undertaken without hope of remuneration. It is not as if no creativity occurred before the first Copyright Act.) Similarly, if we had maximum copyright protection – if rights-holders owned not only expressions but also the ideas upon which they were founded, if we imposed the death penalty for infringement, if term were infinite, if we had no exceptions, if quotations could be taxed, etc. – there would be no creative activity. The costs of licensing would produce an anticommons in which every licensor can say ‘no’, but no one individual can say ‘yes.’ This is because all creative work is slightly derivative – all creators ‘stand on the shoulders of giants’ who came before. Thus, the costs of infringement, inadvertent or otherwise, would outweigh any benefit to creative activity.

Even more conspicuous than the fact that copyright functions as a tax-and-subsidy policy is that we administer IP law in an increasingly micro-managerial manner. This regime today scarcely resembles markets for property, and dramatically resembles how Washington regulates other industries.

Copyright as Regulation

As IP scholars like Mark Lemley have observed, intellectual property law has taken a decidedly regulatory turn in recent decades, which inhibits free competition in the marketplace. My own admittedly anecdotal experience seems to confirm this. I began my legal career practicing both IP and regulatory law, but I was far more interested in the former. While my firm was a fantastic group of lawyers, the regulatory practice was growing faster than the IP work. Not wanting to spend the rest of my career in windowless rooms in the recesses of bureaucracies participating in fights over how the government would circumscribe the conduct of my regulated clients, I went in-house with a client to specialize in intellectual property.

Yet some years later, I found myself in a windowless room in the recesses of the Copyright Office, participating in fights over the Digital Millennium Copyright Act triennial rulemaking process, from which the Librarian of Copyright would issue a Federal Register notice that would dictate the conduct of certain designated groups of users, for a three-year period. I’d been here before: this was regulation. All I could think of was Al Pacino saying, “just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in!”

While I’m at peace with this, it continues to baffle me that more conservatives are not skeptical of expanding intellectual property. What is regulation, if not when bureaucrats hold an administrative rulemaking and issue a triennial rule dictating how individuals must conduct their affairs with respect to media they have already purchased? That sounds a lot like regulation to me.

What is regulation, if not when bureaucracies dispense exclusive entitlements to special petitioners intentionally designed to restrict competition, because it serves the broader purpose of incentivizing the pursuit and disclosure of particular creative activity? This is what our IP law does. Patent law in particular is explicitly conceived as a temporary monopoly, because we assume it will stimulate socially valuable investment if the prize given for coming in first is the government-backed entitlement to stomp on the free market. We’ve taken to calling this whole scheme “property,” in part because (I know from personal experience) it sounds better. People find it a lot more interesting when you say you’re an IP lawyer than when you say you’re a regulatory lawyer. But if copyright is a property right at all, it is the property right to a government subsidy.

The approach of the RSC brief acknowledges this reality. Blinded by the power of the “property” metaphor, we have reached a point where we have too much of a good thing. Unfortunately, it is never easy to be the guy who points out that the Emperor is buck naked, as the RSC discovered over the weekend.

None of this is meant to imply that intellectual property is bad. The regulation of ideas is one of the most important — and dangerous — kinds of regulation in which governments engage. I concede that I am biased, though. After all, I’m a regulatory lawyer.