Streaming, Selling Scarcity And Other Ways To Remix the Music Business

Screengrab of presentation provided by author Jean Cook. Survey and slides are available at: http://money.futureofmusic.org/findings/

The future of independent music doesn’t lie in selling t-shirts and other merchandise, but teaching can be a surprisingly rewarding sideline. Touring can be a net money-loser, but streaming services just might wind up providing a decent chunk of income. And the artists objectively doing worse may feel better about the market’s value of their work.

Those were some of the takeaways from the 2013 Future of Music Summit. This gathering at Georgetown University staged by the Washington-based Future of Music Coalition brought its usual mix of pessimism and hope–not a surprise coming from a group founded in 2000 to speak for artists outside the major-label system and its potential for stratospheric paydays.

(Disclosure: I’ve spoken at FMC summits before, including last year’s).

The conference hit peak despair late Monday morning with a preview of an upcoming documentary, Unsound, that “reveals the dramatic collapse of the music industry.”

(Note that the alleged Hunter S. Thompson quote about the music industry as “a cruel and shallow money trench” that leads off the movie’s trailer is actually a remix of something he wrote about the TV industry.)

Yes, much of the old business model has been blown up, and a lot of artists haven’t figured out how to replace it. But it’s no good to mope about how MP3s, Napster and the iPod ruined everything–those products or things like them were going to be invented anyway. The only question then was what to do next, and vague promises of collective action aren’t enough.

That’s where the summit’s conversations got more interesting–and new research presented Monday provided useful insights on that issue.

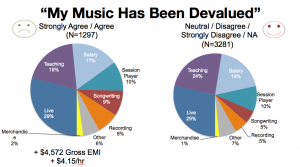

FMC program director Jean Cook outlined how its ongoing online survey of some 5,300 musicians revealed that most did not feel that their music had been devalued–even though they were making less money on average than the artists who felt otherwise–and were staying in business through a diverse assortment of income streams.

- First, you can still make a decent living at this. The musicians surveyed reported an average personal gross income of $34,455–but among the 32 percent working full-time at music, their average was $61,410. Converted to an hourly wage, you get figures varying from $49.43 in Los Angeles (not bad) to $30.06 in New York (time to move to Nashville?).

- Music recordings and live performances make up less of that total than you’d think. The former averaged 5.8 percent of revenue, while the latter averaged 28 percent and can yield minimal or negative net income after touring expenses. Sales of t-shirts and other “merch” were inconsequential, but teaching and session work–both activities protected indirectly at best by copyright law, but also “sell the scarcity” activities not easily duplicated as an online bitstream–added up to 22.4 and 10.2 percent of gross income.

- The 1,297 respondents to say their work had been devalued (“Sad Sams,” in Cook’s phrasing) relied more heavily on income from compositions and recordings than the 3,281 “Happy Harrys” who were either neutral on the issue or disagreed with the devaluation statement. But the Sad Sams averaged $4,572 more in gross musical income than the Happy Harrys.

Is selling music therefore doomed as a business? Not necessarily.

Set aside the occasional wishes for a copyright levy to be applied to Internet access–like the “private copying” levy Canadians pay on blank recording media, with the added obstacle of being fairly labeled as “taxing the Internet”–and two less politically implausible possibilities emerged.

One would be a belated outbreak of fairness in performance royalties paid to musicians. Instead of decrying Web-radio broadcasters such as Pandora that have been struggling for years to have their disproportionately high rates reduced, FMC speakers supported lower but broader performance royalties. As in, having now-exempt FM stations start paying them instead of only providing royalties to songwriters whose work gets a spin on the air.

Another was the promise of turning streaming music services–not just Pandora but also on-demand apps like Spotify–into a solid revenue stream.

This conversation started out with the usual Spotify-pays-squat attack; Songwriters Association of Canada president Eddie Schwartz (also the author of Pat Benatar’s “Hit Me With Your Best Shot”) cited a per-stream rate of $.000035 there to say “in effect, there is no difference between piracy and legitimate streaming services at this point.”

But a few hours later, music marketer David Macias pointed out some other relevant angles. The co-founder of the Nashville firm Thirty Tigers observed that Spotify only constitutes three to four percent of the music market–and in Sweden, where it’s more like 75 percent, “revenues have gone up every single year by double digits and a lot of independent artists are making a lot of money.”

(Macias expanded on this view in a July op-ed at Billboard.)

Streaming services, in turn, are best understood as a first level of a pyramid of music consumption in which fewer people spend more time and money on the artists they love, argued Google Play Store music guru Tim Quirk.

“The same song will always be worth different things to different people at different times,” said the onetime Too Much Joy frontman. The trick is to find what music moves any one group of fans, then make it easy for them to deepen that interest: “Catching people’s attention and then hanging on to it is the fundamental challenge for artists in the 21st century.”