Adventures In Copyright: Formula One, Football, Google Books and Fair Use

Project DisCo readers know that a number of our contributors have regularly posted on the subjects of copyright and fair use. Indeed, the topic is not only important, but one for which change is frequent and sometimes lurching. Nothing exemplifies that better than the shifting sands of copyright enforcement by major U.S. and international sports organizations, like the National Football League and Formula 1, in today’s age of social media.

I’ve been a passionate fan of both sports for decades, since the “British Invasion” of Indianapolis with rear-engined race cars of 1963-65 and the Green Bay Packers’ dominance of professional football throughout the 1960s. In those days, of course, there were no VCRs, DVRs or digital media available to consumers and fans. And as NFL aficionados recognize, each television broadcast on Sunday (and Thursday or Monday) is preceded by a conspicuous copyright notice cautioning that except for private viewing, “any other use of this telecast or any pictures, descriptions or accounts of the game without the NFL’s consent is prohibited.”

That “prohibition,” Ars Technica observed, is “wrongheaded.” Almost alone among Western nations, the United States has enshrined fair use by statute into the very fabric of copyright law. Fair use permits one to publish excerpts of a copyrighted work legally, by application of a multi-criteria test focusing on the “purpose and character” of the use, the nature of the copyrighted work, the ”amount and substantiality” of the portion used and “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” Thus, fair use of a copyrighted work, “for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship or research, is not an infringement of copyright.” The NFL can no more prohibit newspapers, or bloggers, from publishing an “account” of pro football games than the company owning rights to the Ed Sullivan Show could prevent use in a Broadway production of a 7-second clip from a 1966 episode depicting introduction of the Four Seasons musical act.

Congress’s guidance, however, has not always been helpful. As the Ninth Circuit cogently summarized, “[m]any fair use cases still manage to approach ‘the metaphysics of the law, where the distinctions are, or at least may be, very subtle and refined, and, sometimes, almost evanescent.’” And as the Copyright Office itself acknowledges, “the distinction between fair use and infringement may be unclear and not easily defined. There is no specific number of words, lines, or notes that may safely be taken without permission… The Copyright Office can neither determine if a certain use may be considered fair nor advise on possible copyright violations.”

There’s nothing new there, of course. What is different is that as social media and digital technology proliferated by an order of magnitude over the past 10 years, copyright holders became more aggressive in challenging “unauthorized” use of their works. For years, Formula 1 routinely issued DMCA takedown notices to any YouTube user who posted a video containing any images of an F1 grand prix race. I’ve been a target of this officiousness — what I derisively termed “Bernie Ecclestone’s copyright Nazis” — for instance after posting a brief clip of a tremendous (and safe) inverted crash by Red Bull Racing’s Mark Webber at the 2010 Spanish Grand Prix. F1 also protected its copyright claims technologically by making “official” video race highlights available only via locked-down Adobe Flash files.

So what has changed? First, Formula 1 abandoned Flash this season and now regularly posts photos, videos and updates in the clear via Twitter. Not only does that enable permissible (and permissionless) sharing of such media by embedding tweets, it also raises serious questions of whether making purportedly copyrighted works available to the world, without protection, equates to an implied copyright license. Second, the National Football League launched the 24/7 NFL Network, and with it online streams of game highlights, thus making pure digital copies of its copyrighted properties available for transformative uses — long a permissible fair use exception to the reach of a copyright holder’s right to exclusivity. Third, the NFL has followed F1’s lead in making game highlights available freely via its Twitter feed (under a lucrative deal with Twitter). Fourth, even some publishers (Fox, for instance) have now embraced the “unique, transformative nature of social media” as a fair use justification for repurposing content for near real-time consumption.

Most significantly, perhaps, the federal courts have been more protective of fair use, with major recent decisions upholding Google’s book-scanning project and, more provocatively, imposing a duty of fair use investigation on copyright holders, such as Universal Music, invoking the DMCA’s takedown procedures. As EFF complained:

It took eight years of litigation to get to this point. That’s right: it took eight years to establish that record labels like Universal must consider whether your speech is legal before they try to get it taken off the Internet. We are glad to finally have this result and we hope that this ruling will lead to less takedown abuse in the future.

Conservative pundits, in contrast, label the Ninth Circuit’s Lenz v. Universal Music Corp. decision “a takedown of common sense.”

Currently, rightsholders send out tens of millions of takedown notices every year to deal with the flood of piracy and other infringing uses. If rights holders were required to consider fair use in advance of each of these, the system would be utterly unworkable — for instance, in Google’s search engine alone, over 54 million removal requests were made in just the month of August 2015 owing to potential copyright violations. While the evisceration of the DMCA is, of course, exactly what the plaintiffs (or more accurately, EFF, which represented the plaintiffs) in Lenz wanted, it’s not remotely what the hard-wrought compromise of the statute contemplates.

Some of the turmoil relates to the legal safe harbor granted ISPs and web sites from copyright liability for hosted user-generated content (UGC) under the DMCA, which immunizes those entities if they promptly take down UGC upon a notice of claimed infringement. YouTube, Facebook, Twitter and the like, all of which rely largely or entirely on monetizing UGC, simply cannot afford the legal risks — up to $150,000 per incident — that are possible when the issue is the “metaphysical” one of fair use. So they naturally remove virtually all content challenged by copyright owners. One group of professional photographers has gone so far as to ridicule fair use as the “F-U” defense. Whether Lenz and its potential for recovery of attorneys’ fees and nominal damages by users who post fair use excerpts of copyrighted works fundamentally changes that equation of course remains to be seen.

The newest battlefield changing the dynamics of fair use is GIFs. Long-time Web users recall that, before the advent of Cascading Style Sheets, GIF images were frequently used as buttons and related navigation links in website design. They’ve recently witnessed a comeback, fueled once again by social media and sharing services like Vine, as users convert brief clips of copyrighted works into 3-6 second animated GIF images. (Technically, Vines are similar to GIFs as they are short and focused video clips, but use a proprietary digital format owned by Twitter.)

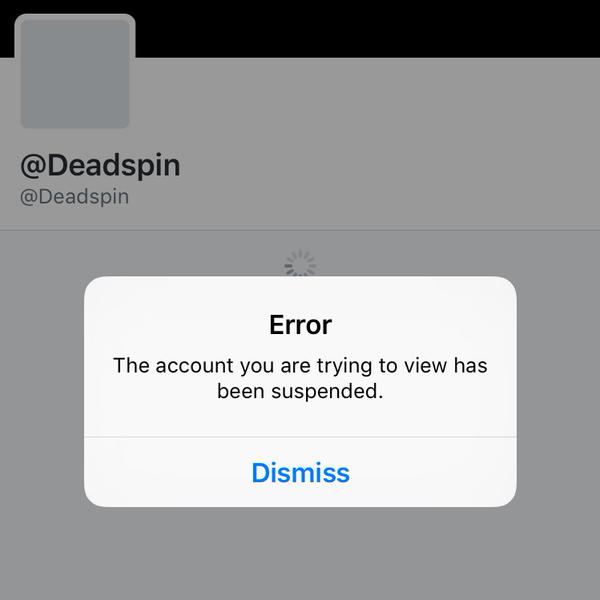

Just last week there was a tremendous uproar when the NFL issued DMCA takedown notices against two well-known sports reporting blog services that posted GIF animations of exciting pro football plays on Twitter. While major media, such as the Boston Globe, routinely use GIF animations in their own sports coverage — and many other GIF clips of NFL action remain online, including through new sharing sites like Giphy — the NFL’s attack on GIF clips raises public relations as well as legal issues. Dubbed by some as a “losing battle,” that’s unfortunately not certain. On the one hand, as the Four Seasons court concluded, “[i]t is doubtful that [7-second] clip on its own qualifies for copyright protection, much less as a qualitatively significant segment of the overall [Ed Sullivan Show] episode.” Moreover, animated GIFs have no audio, represent a small fraction of the copyrighted work, and often include other transformative or parody elements, such as Dez Bryant slipping on a banana peel in the end zone or celebrating a team’s success. And they enable a qualitatively different form of immediate sharing of and reaction to sporting events in a way not possible with traditional television and media. Conversely, there is a thriving commercial market for NFL highlights, the majority of which are licensed by ESPN and the like for their use in broadcast and Web programming.

How those competing interests are balanced in the context of fair use, as always, remains to be seen. For its part, Forbes commented that

unlike curating articles from other news organizations, and likely taking a share of their audience, it’s difficult to see how sharing brief copyrighted videos harms sports leagues’ bottom lines. Judging by the NFL’s monstrous television ratings, it doesn’t seem as if fans are tuning out because they can watch six-second Vines on Twitter.

The issue here is not just ownership of UGC — for which I’ve previously observed that the law “muddles along while the status of user-generated content remains in limbo, as newer developments like embedding of Twitter content (including linked photos) make social media’s copyright dilemma ‘even weirder’” — but instead the delicate balance between copyright protection and creative expression struck by Congress in codifying the common law fair use doctrine. CCIA, the sponsor of Project DisCo, made this precise point nearly a decade ago in 2007, when it filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission arguing that over-broad copyright warnings and takedown notices violated Section 5 of the FTC Act by “misrepresenting consumers’ rights to use copyrighted works and by threatening sanctions for lawful uses of those copyrighted works.” Groups representing 139,000 U.S. libraries supported the CCIA complaint.

The FTC has been aggressive in pursuing privacy violations and data security breaches under Section 5, but declined to take action on the CCIA complaint. The agency said in response that “consumer confusion” could equally be a consequence of the vagaries of fair use law. It also predicted that “changes in content delivery mechanisms, business models and the nature of consumers’ interactions with copyrighted works will likely result in this issue taking on added significance, particularly given the increasing number of lawsuits brought against consumers for copyright infringement.” That likelihood is real now, given a major boost in visibility by the nation’s most popular, profitable and ubiquitous professional sports league.

Unlike Deflategate and Tom Brady, however, there is no collective bargaining organization representing the interests of sports fans who share NFL action excerpts, whether by GIFs or otherwise. Maybe there should be. The way in which sports fans consume game clips is rapidly changing. They watch videos in real time instead of waiting for networks to air highlight packages. And with cord-cutting on the rise, it seems unlikely that this pattern is going to change. As Forbes noted, “the leagues that continue to fight this shift in the market don’t only look antiquated, but they may lose out on connecting with potential consumers. Almost any publicity is good publicity, especially when it comes in the form of viral videos that are shared on social media.” Roger Goodell, the current NFL Commissioner, might want to take a lesson from F1’s impresario Bernie Ecclestone.

All of this will be informed by the Second Circuit’s landmark decision last week in The Authors Guild v. Google, Inc., which upheld Google’s automated scanning of copyrighted books, and display of “snippets” in Web search results, as “highly transformative” and not threatening to the commercial interests of books publishers or authors. “Many of the most universally accepted forms of fair use, such as news reporting and commentary, quotation in historical or analytic books, reviews of books, and performances, as well as parody, are all normally done commercially for profit,” wrote Judge Pierre N. Leval in his opinion for the appeals court. Yet the court prominently cautioned that the case “tests the boundaries of fair use.”

Yes, indeed. Like the NFL and Formula 1, new technology is pressing the limits of fair use, but from the user’s side. Stay tuned for more adventures in the shifting sands of copyright as the balance between rights owners and “fair users” lurches along towards more high-profile showdowns in the future.