NetNames Piracy Study Yields Same Lesson As Old: Legal Options Shrink Infringement’s Share

A paper released Tuesday shows that the entertainment industry continues to be menaced by cheapskates who spend much of their time and bandwidth on pirate sites.

A paper released Tuesday shows that the entertainment industry continues to be menaced by cheapskates who spend much of their time and bandwidth on pirate sites.

Another study–weirdly enough, also released Tuesday–shows that Hollywood’s digital future looks more secure as wider access to legitimate content drives down infringement’s share of the market.

No, the two documents aren’t actually the same. One is a four-page summary of research conducted by the London firm NetNames for NBC Universal and presented by the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation at an event Monday in Washington. The other is the full 100-page “Sizing the piracy universe” study.

Both represent a sequel to a similar project conducted in 2011. Back then, NetNames–then known as Envisional–presented it as proof that creative types were in trouble, but which I read as confirmation that you can compete with “free” if you make legitimate content available at reasonable terms.

Two years later, the song and dance remains much the same. NetNames presents some noteworthy data points–without so many of the questionable assumptions about what constituted “infringing” content that marred the 2011 study–but leaves out basic context in the hope that raw numbers will top the headlines.

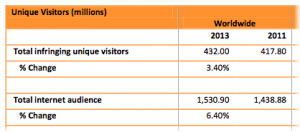

Take the stat that leads off NetNames’ press release: “432.0m unique internet users explicitly sought infringing content during January 2013.”

You have to read to the third-to-last page of the full study to learn that 432 million is less than 29 percent of all Internet users that month–a bit over 1.53 billion, per ComScore estimates–and that the infringing population grew at a lower rate than the total Internet population between 2011 and 2013. Presenting a sort of math in which fractions arrive devoid of denominators does not invite confidence in the results.

You also have to read to page 80 to determine that those 432 million ne’er-do-wells include anybody “who downloaded or viewed at least one piece of infringing content” in January 2013.

As any look at the average airlines’s boarding process will remind you, not all customers are equally valuable. It would have been more informative to focus on habitual downloaders.

The complete report does make clear that things are better in the U.S., thanks to the much easier availability of legitimately sourced movies, TV shows and music online here. This paragraph from page 27 should be instructive:

“It is clear that the downstream landscape in North America is significantly different to the other two regions, dominated by the legitimate video streaming service Netflix which consumes 29.1% of downstream bandwidth in the region. It is also interesting to see that iTunes, another legitimate service, is the fifth placed individual protocol for downstream bandwidth consumption in North America.”

A pie chart two pages later breaking down NetNames’ estimates of infringing use on BitTorrent–what it identifies as the largest such venue on this continent–provides a little more illumination. It shows movies making up 33.4 percent of 12,500 popular torrents, pornography made up 30.3 percent, TV shows 15.3 percent and music just 7.6 percent.

Unmentioned but relevant: It is overwhelmingly easier to find music you want and either pay about a dollar to download it–without any “digital rights management” interference–or pay nothing to stream it.

Video, however, remains harder to find on legitimate terms. The study unintentionally reminds readers of that fact on page 39 by citing the easy availability of Despicable Me 2 on streaming-video sites. You can’t even buy a DVD of the flick on Amazon, much less download or stream it on that site, Netflix or iTunes.

The report is surprisingly thin on policy prescriptions, aside from a couple of vague suggestions that copyright holders need “access to tools and methods that allow them to react no less quickly as users and site operators do to changes and transformations in the different piracy ecosystems.”

(If by that the authors mean a renewed campaign to pass some souped-up version of the Stop Online Piracy Act: Good luck! You’ll need it!)

But a careful reading of its analysis of the movement of infringing content from centralized file-sharing sites and networks to the widely distributed medium of BitTorrent suggests the futility of focusing on technological or legal solutions.

Enforcement actions based on existing laws–such as the 2012 seizure and shutdown of MegaUpload, praised more than once in the report–have worked, but they’ve also helped ensure that infringement migrated to the most resilient system available.

It’s better to get in the market with a reasonable offer, as this report clearly suggests if you read the whole thing. I have to give NetNames credit for prominently linking to that in its own release. And for resisting the temptation to package its headline findings in yet another visually appealing but misleading infographic.