“Cheap iPhone” Coverage Shows The Pernicious Persistence of Price Shifting

Apple introduced two new iPhones yesterday, and much of the early buzz has been about the model that costs a little less than its predecessor.

Apple introduced two new iPhones yesterday, and much of the early buzz has been about the model that costs a little less than its predecessor.

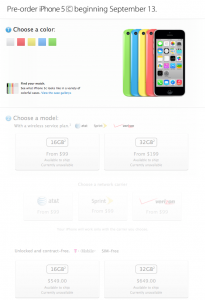

Never mind the iPhone 5c’s choice of five vibrant colors or improved front camera; its most important feature is apparently its lower price. The Associated Press, NPR and NBC News all put “cheap,” “cheaper” or “$99” in the headlines or near the top of stories that keyed in on Apple’s touted price for a 16-gigabyte iPhone 5c.

But those stories–as well as Apple’s keynote presentation in Cupertino and its press release–didn’t mention the real price of the 5c. That is not $99 but $549, what you pay if you buy it without a contract.

And $549 isn’t all that cheap. It’s only $100 less than the unsubsidized price for the iPhone 5s or today’s subsidy-free price for an iPhone 5. Even the two-year-old iPhone 4S’s advertised $0 contract price turns out to be a full $450 without one.

For years, U.S. buyers could skip the extra math involved to back out the real price of a phone. Everybody subsidized the upfront cost, then made it up in higher rates that didn’t drop after the subsidy had been recouped.

But since T-Mobile ended subsidies, instead letting buyers choose between making no-interest installment-plan payments or paying the phone off upfront, pricing has gotten a lot more transparent.

Or it should, except so many people continue to forget how subsidies distort the market.

It’s not just a case of customers getting gouged by paying for a long-since-recouped subsidy. (A friend who confessed yesterday that he still has an iPhone 4 could have donated more than $250 this way.)

Subsidies also mean the phone effectively remains your carrier’s property. If you want it unlocked to use with another carrier–assuming it operates on the GSM standard, which permits this portability–you’ll either need to ask nicely or, at worst, wait until you conclude your contract.

At home, locked phones ensure you can’t fire your carrier without dumping your hardware. Overseas, they restrict you to paying expensive roaming rates or giving up use of your phone outright. At the IFA trade show in Berlin last week, I was surprised to see so many U.S. tech journalists limping along on WiFi, with their phones otherwise locked in airplane mode until they returned to the States.

And for manufacturers, leaning too heavily on the crutch of subsidized prices puts them at an immediate disadvantage in international markets where buyers either have smaller budgets or few carriers play that game.

Apple, for instance, is already taking criticism for pricing the 5c too high for the vast Chinese market.

That company will probably do fine in other markets, where carriers find that more expensive iPhones still generate more than enough profit margin. (If you don’t understand that Apple pursues profit share before market share, little of what this company does will make sense.) But most manufacturers can’t bank on the enthusiasm and loyalty of contented iPhone users.

And those who assume that carriers can perpetually sweep the true price of a phone into a monthly bill risk getting undercut. If Google can get away with selling the Nexus 4 at the ridiculously good unlocked price of $199 (it was a steal when I paid $100 more in March) and Nokia could ship a capable Windows Phone model, its Lumia 521, for $150, other competitors can join that game too.

In the meantime, you as a potential customer have one other reason to be wary of coverage that doesn’t mention the full price of a phone: If that didn’t make the story, what other key details did the piece miss?