Why Antitrust Immunities Are Bad Public Policy

Policymakers, regulators, and enforcers are grappling with concerns related to the fact that disruptive competition is disruptive. Innovations brought by the tech industry have caused markets to change. While new forms of competition often leave consumers better off, disrupting beloved industries can sometimes be painful. One industry that has come up consistently in this context is the journalism industry, which has been in a decades-long transitional period.

As a policy matter, there may sometimes be a good argument for using government to try to resolve transitional problems related to disruptive competition. In DC, we hear debates on this topic often, and concerned parties have identified many tools to consider using for this purpose. However, one proposed tool that has consistently raised significant concerns is expanding the antitrust immunities available for news publishers.

I wrote about what antitrust immunities are in previous posts [1, 2]. However, in this post I hope to apply the history of antitrust immunities to show how they can be tempting but generally a bad idea.

We’ve Been Here Before

It’s easy to forget that technology has regularly disrupted the news industry. Video may have killed the radio star, but radio was the first disruptor. During the ’20s and ’30s radio came into its own as a national competitor to the printed news. Newspapers were forced to adjust, and revamped their formats, added more in-depth reporting, and started offering things radio couldn’t like comics and weekend magazines. Competition from televised news in the ’50s again forced newspapers to adapt. Some, like USA Today, adopted color newsprint and short, to the point stories. Others focused on feature stories and detailed analysis pieces. Newspapers also focused on bringing their costs down. Competition from televised news may have led to the death of afternoon papers, but newspapers adapted to remain strong competitors.

However, news companies were engaging in behaviors considered anticompetitive during these periods of transition. Antitrust cases challenging these behaviors, like Associated Press v. United States and Lorain Journal Co. v. United States, are still considered by antitrust scholars as some of the most important decisions in all of antitrust case law. In response to one of these cases, Citizen Publishing Co. v. United States, Congress granted a partial antitrust immunity to newspaper publishers. The case concerned competing newspapers who set up joint operating agreements (JOAs) that, while providing some cost savings, enabled cartel-like pricing. The Newspaper Preservation Act (NPA) was passed to grant antitrust immunity to certain JOAs formed before its passage and extended immunity to new JOAs “in probable danger of financial failure” in certain circumstances. The NPA allowed JOAs to collectively set circulation and advertising rates if, among other things, they preserve separate editorial boards.

The Response to Calls for Additional Antitrust Exemptions Has Been Critical

In 2011, Christine Varney, speaking as the then-head of the Antitrust Division, gave a speech critical of new calls for expanding antitrust immunities for news publishers. Varney stated “[t]hese well-intentioned, but ultimately misguided, attempts to permit otherwise illegal behavior correctly have not been adopted” and stressed that vigorous competition on the merits “best serves the interests of consumers.” Varney went on to agree with the Antitrust Modernization Commission’s “conclusion that departures from this maxim of our free enterprise system should be rare because they tend to benefit a small minority of economic actors at the expense of consumers in the form of higher prices, reduced output, lower quality, and reduced innovation.” (The Antitrust Modernization Commission’s report was covered in the statutory exemptions post).

Antitrust scholars Maurice Stucke and Allen Grunes went further, publishing an essay called “Why More Antitrust Immunity for the Media is a Bad Idea.” The essay singles the NPA out specifically as being a good example of why antitrust immunity for the media is a bad idea. The essay argues that the NPA largely originated from a lobbying effort by major newspaper owner the Hearst Corporation. The NPA was heavily opposed by the DOJ and Richard McLaren, the then-head of the Antitrust Division. The essay notes several failings of the NPA: it mainly benefited large newspapers rather than the smaller papers intended, JOAs incentivized some smaller papers to shut down in exchange for a share of the surviving papers’ profits, and it has not seemed to improve editorial quality (some beneficiaries were actually criticized for their poor quality after NPA passed). The essay also catalogs some very questionable behavior by Hearst in the San Francisco market that is too lengthy to summarize here, but worth reading.

Essentially, the NPA has not appeared to help much and may actually have condoned bad behavior. JOAs haven’t even proven to be useful in today’s news industry. Today only about five JOAs exist, down from twenty-two in 1969.

The Transition Marches On

The continued and rapid evolution of the journalism industry is itself a good reason why trying to draft additional antitrust exemptions is a bad idea. In the past few decades we’ve seen tremendous changes in how Americans get their news. The sources are changing. We’ve gone from a largely journalist-driven news market to one where it is common to mix reporters and pundits. At one point 12% of online Americans cited Jon Stewart’s The Daily Show as where they got their news, and it was more trusted than MSNBC. Today there is a comedy news program on Netflix called Patriot Act. News aggregators are also playing an increasing role in how Americans find news. These include social aggregators like Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit. It also includes news-focused aggregators like Google News. There is more competition from smaller news sources, including online-only publications that cater to specific interests. It would be extremely difficult to capture this rapidly changing environment in legislative text.

At the same time, antitrust laws have evolved to permit legitimate behavior that was once condemned. The NPA was partially created to allow new JOAs when a company is “in probable danger of financial failure.” But as Varney notes, the failing firm defense has been available to justify mergers of competitors for some time now. Varney also pointed to several business review letters that “illustrate the Division’s agile approach to newspaper collaborations.” The business review letter is a way for any company to request a review of proposed conduct and the Antitrust Division will state its enforcement intentions with respect to that proposed conduct. The Antitrust Division has issued several letters on media proposals stating no present intention to challenge the conduct and noting potential procompetitive benefits.

Another major problem is that antitrust immunities often rely on the idea of countervailing power, balancing one party’s negotiating leverage by increasing another’s. But this idea is widely criticized when raised as a defense in merger challenges under the Clayton Act. This is because creating monopoly power to balance alleged monopoly power somewhere else in the supply chain only multiplies your monopoly problems.

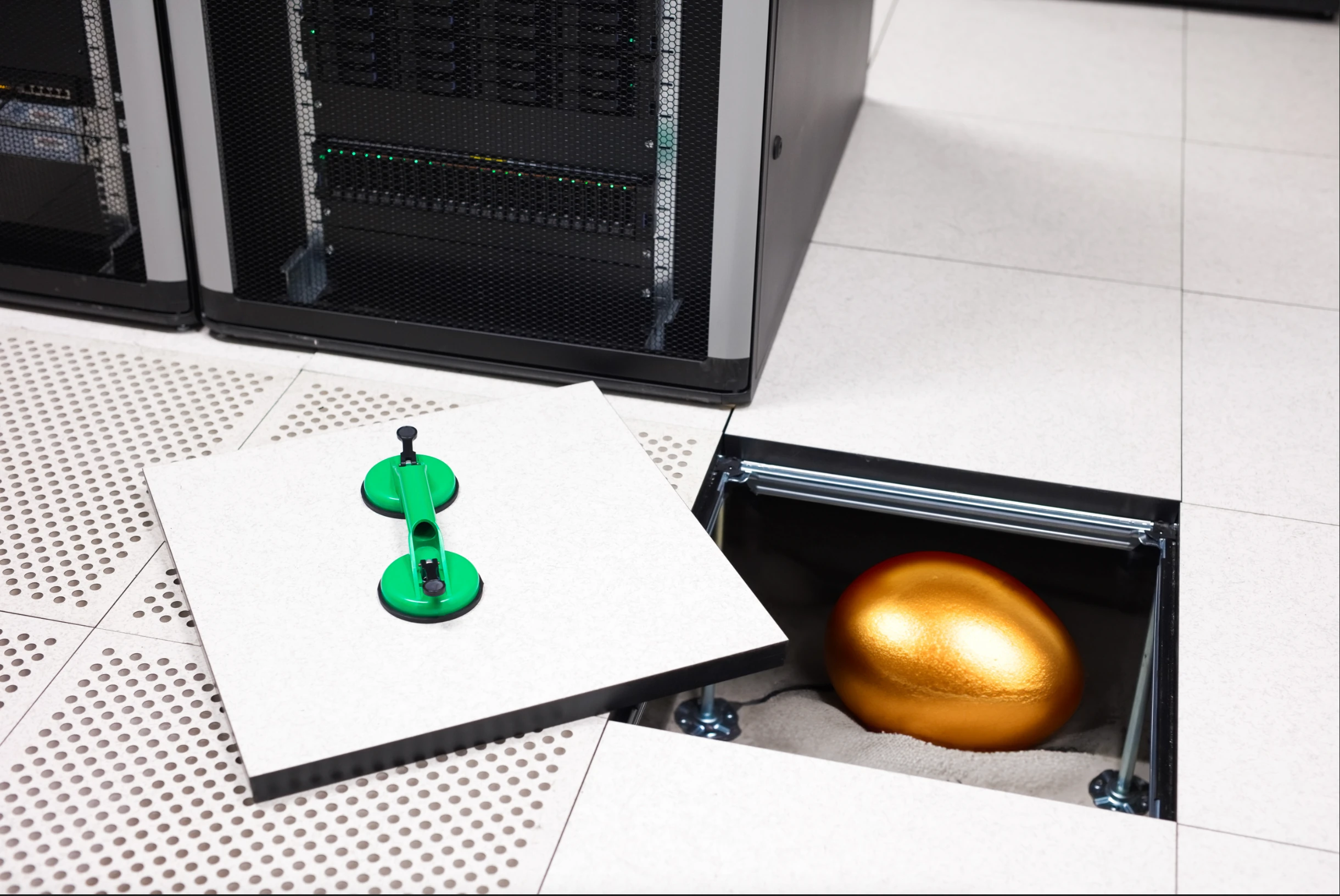

Finally, it might be too soon for legislation. There are multiple different efforts to figure out how to create sustainable journalism in this new transitional period. ProPublica is an award-winning nonprofit newsroom that delivers in-depth investigative reporting. Some internet companies are also investing in finding ways to help journalism transition to this new era. Facebook just this year announced a $300 million investment in local news initiatives. Google has launched its own Google News Initiative.

Conclusion

History has shown us that there are at least three clear problems that come from statutory antitrust immunities: 1) they support bad behavior and gaming by special interests; 2) they do not respond to market changes; and 3) once enacted they become almost impossible to repeal. I see no reason why they will be any better this time around.