Homebrewed Innovation: What Can Beer Teach Us About Regulation and Innovation

We’ve been a little boozy here at DisCo this summer. Recently, my much classier colleague, Matt Schruers, dissected how creativity and innovation prosper in the high-end mixology market without intellectual property protection. I’ll have to take his word on it, as they don’t let me into the joints where bartenders rock throwback suspenders (braces?) and well coiffed handlebar mustaches and hock haute couture cocktails for prices that are anything but retro, unless, of course, you were buying a Buick.

Instead I turn my attention to an alcohol more up my alley, the potent potable of the proletariat: beer. Although one hardly associates a beverage that dates back to the Neolithic period with innovation, the history of beer can teach us a lot about the positive and negative effects of regulation and the benefits of decentralized creative forces.

Specifically, let’s look at the originator of the modern oat soda, Germany. Germany has long been viewed as a hop-head’s heaven and home some of the best brewers in the world. Not only did modern beer originate in Germany (first documented use of hops), but for 16 days every fall millions of pilsner pilgrims from all over the planet pay homage to the historical homeland of hops by flocking en masse to Munich for the biggest bacchanal bash on the planet (aka Oktoberfest). In fact, Germany consumes the second most beer per capita in the world, with the average German consuming 107 liters of beer per year.

Unfortunately for German brewers, the 107 liters per year represents a 10% decrease in average beer consumption over the past decade. Although German physicians might consider this good news, German brewers are concerned. Many have blamed “boring beer” for the annual decline in beer consumption. Furthermore, foreign imports, once a trivial part of Germany’s beer market, are growing in popularity and now make up over 8% of the German beer market. One of the fastest growing imports by volume are American craft beers and microbrews. Germans paying a premium to import American beer; has the world gone mad? Maybe. But maybe the boring beer has something to do with it.

And before you go all Jared Diamond or Max Weber on me and say that the explanation for why there is so little variety in the German beer market is explained by the natural endowments of Northern European landscape or the cultural heritage of the populace, Germany’s neighbor, Belgium, is famous for its freewheeling beer culture and the tiny country boasts over 450 different varieties of beer. In Germany, however, one beer — pilsner — accounts for over 50% of beer sales (that’s not to say that its not really good pilsner).

The Origins of Orthodoxy

Rewind to 16th Century Bavaria, when Duke William IV adopted the Reinheitsgebot, or “beer purity law.” Although much of the law was devoted to setting a standard price for beer, it contained a prescriptive regulation as to the content of the beer: “the only ingredients used for the brewing of beer must be Barley, Hops and Water.” Later updated to include yeast, when Louis Pasteur discovered the role of microorganisms, and not magic, in the fermentation process.

Now, in 16th century Bavaria, these particular regulations did indeed serve a purpose, as price sensitive brewers would often replace hops with other more questionable preservatives, such as soot and poisonous mushrooms. Furthermore, the law limited brewers to using barley malt while preserving wheat and rye for bread making (or special wheat beer for the nobility). As the Washington Post notes, the law also had a downside; it limited innovation:

As a consumer protection law (perhaps the world’s first), the Reinheitsgebot has kept German beer free of such noxious adulterants as narcotic herbs and chemical preservatives as well as the corn and rice adjuncts used to lighten mass-market beer. But it also has prevented German brewers from experimenting with such flavor enhancers as fruits, herbs, spices, and exotic grains.

However, as is the case with many regulations, the Reinheitsgebot also had a more sinister anticompetitive side. Strict regulations forbidding many ingredients from being in beer protected brewers from competition from outside Bavaria. In fact, Bavaria made adopting the Reinheitsgebot a precondition of German Unification in order to maintain its protected market. Fortunately Germans would be ostensibly protected from unknowingly drinking poisonous mushroom extract. Unfortunately, the nationwide adoption of the purity regulation led to the extinction of regional craft beers in other (i.e. non-Bavarian) parts of the new German state. Instead, pilsner became the near ubiquitous beer of Germany. (In fact, some argue it turned beer into a commodity in Germany).

In 20th century Germany, brewer’s guild regulations and local laws perpetuated the Reinheitsgebot standards, and they were eventually included in the national law of West Germany, and even in the post 1990 law of reunified Germany (albeit in the slightly watered-down form of the Provisional German Beer Law). In fact the “Brandenburg Beer War,” which involved the government taking legal action against a local brewer for including non-Reinheitsgebot ingredients (in this case, sugar) in its beer, lasted most of the 1990s and early 2000s. (Ironically, when the brewer threatened to stop paying the beer tax after he could no longer market the product as “beer,” the tax ministry objected.)

So, even though the Reinheitsgebot is no longer officially on the books, and the new German law allows for some experimentation, German brewers have been slow to evolve beyond their tried and true, albeit homogenous, standards. As one group of authors writes in Wharton’s Online Business Journal, strict adherence to one standard over hundreds of years has had profound effects on the innovative culture of German’s brewing community:

Although the Reinheitsgebot has been replaced, it may have dissuaded German breweries from experimenting and innovating. This was a gold standard for the taste and quality of beer, and brewers followed it to the letter; additions of any type were strictly prohibited. German tastes also began to conform to this law. While demand was growing, the breweries did little to invest in innovation. As a result, today there are only about 20 common styles used for brewing in Germany, whereas craft brewers in the U.S. are working on at least 100, according to slate.com.

The Microbrew Revolution

The rise of American beer sales in Germany would have been inconceivable even a decade ago. America, quite rightly, was viewed by the old world as the land of watery, corporate beer designed to be (barely) palatable across the full spectrum of American taste buds. As the BBC recently wrote, “[n]ot so very long ago, American beer was a joke. And a weak one at that.”

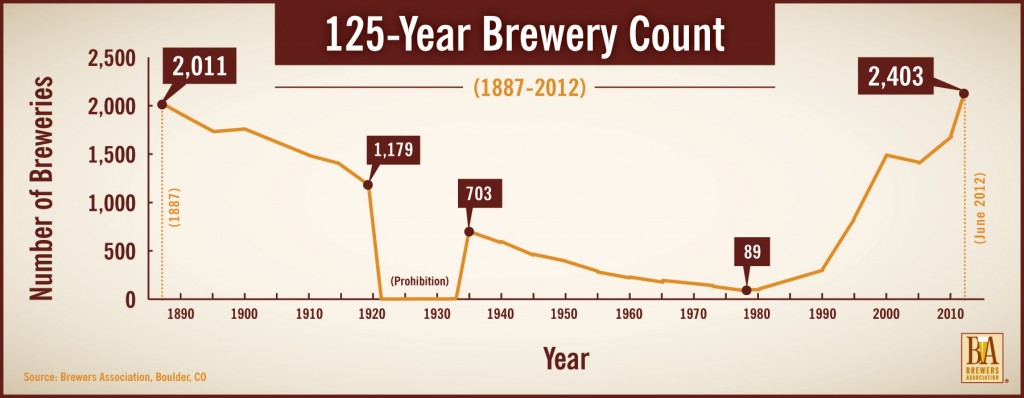

However, with no historical or legal anchors preventing freewheeling experimentation, the bland, ubiquitous mass market beer scene provoked a backlash that lead to the decentralized growth of homebrewers and small craft breweries throughout the United States beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s. What started as a niche scene exploded in popularity in the early 1990s and again in 2005. Now, according to the Brewers Association, the U.S. market boasts 2,538 breweries (up from 50 in 1980), more than any other country in the world. Furthermore, the ranks of American homebrewers have swelled to nearly 1 million people as of 2012.

This dynamic U.S. beer market is translating into economic payoff. Last year, American craft beer exports increased by 72%. Now, not only is American craft beer increasing in popularity in Germany, but in other European countries, such as the United Kingdom and Sweden, that have strong historical national beer identities.

Although the German pilsner purist might scoff at the dizzying growth of non-traditional beers and view it as heresy, it is hard to argue with international demand. Although German beer exports have increased since the 1990s to around 15% of their total production, it still pales in comparison to their more innovative neighbor, Belgium, who exports nearly 60% of their total beer production (representing a 70% growth over the past decade).

As Eric Ottaway, the General manager of Brooklyn Brewery, points out, “[t]he German beer industry has to reinvent itself in a hurry, or it’s going to be a small fraction of what it is now.”

And Eric knows what he is talking about. The New York City Craft Brewery which began in 1987 is one of the most successful in the United States — they contend to be the most exported craft beer in the United States — and is also expanding its exports aggressively in Europe. The beer is selling successfully in Germany, despite costing German consumers three times as much as it does in the United States.

Distilling the Moral of this Story

Although regulations and government imposed standards can be a good thing — protecting you from poisonous fungi and soot in your brew — they can also have profound effect on innovation. Well-crafted regulations should be narrowly tailored and leave room for market forces to spur individual ingenuity and innovation. Furthermore, inflexible standards may soon become out of date as technology and knowledge evolve (like when yeast was discovered). Perhaps Germany would have been better served by laws that prevented poisonous plants or soot in beer, as opposed to a law that prescribed everything that was allowed in beer. Sure, innovation happened within the standard (German brewers became really good at making a small subset of lagers), but now Germany is left scrambling to catch up as the tastebuds of the international marketplace have evolved. German brewers are rightly scared about losing their status (and market share) as being among the world’s elite beer makers.

Furthermore, the homebrewing revolution and the rise of small, independent brewers also has strong parallels to the rise of Silicon Valley. In Annalee Saxenian’s classic book Regional Advantage (a must read for students of innovation policy), she uses the natural experiment of comparing the development of the Route 128 corridor outside of Boston to Silicon Valley. Although both regions had similar endowments of talent and investment, the Route 128 corridor stagnated while Silicon Valley prospered into the arguably the biggest success story in the history of innovation. As Saxenian illustrates, the different outcomes had a lot to do with Silicon Valley’s vast network of small firms and decentralized focal points of innovation that frequently cross pollinated each other with talent and swapped ideas back and forth. In the Route 128 corridor, the original hub of commercial tech innovation in the United States, the story was quite the opposite. Innovation was tightly controlled and centrally planned inside large, secretive corporations (such as DEC) and sharing of ideas and talent was culturally and legally discouraged.

The parallels between Boston and Silicon Valley and the tale of the German and the American beer markets are pretty striking. The dynamic, decentralized U.S. brewing market spawned enormous choice and innovation, much like the decentralized innovation culture of Silicon Valley. Perhaps, then, it should come as no surprise that the famous Silicon Valley group of computer hobbyists and hackers whose members (including Steve Wozniak) would help lead the PC revolution (and rise to Hollywood fame in the Pirates of Silicon Valley) chose to call their group the Homebrew Computer Club.